Scratches, dings, dents, and fading are merit badges on the sash of authenticity and whether a watch was jettisoned into the stratosphere or saw the depths of the oceans, the potential for a watch to have reached environs virtually uninhabitable by man imbues it with a mystique and aura that watch collectors obsess over. Recently, a dive watch from the ‘60s with a unique engraving captured my imagination, and I quickly worked to acquire the piece and immediately began digging into its history.

The watch in question is a vintage Aquastar 63, which was named for the year in which it was introduced. My brother, who is a biologist, fellow watch collector, and all around good guy, tipped me off to the Aquastar 63 and was the first of us to note the watch’s subtle caseback inscription. The watch was listed on a popular auction site and the listing itself made no mention of the engraving other than stating “there is also a small dedication on the caseback.” However, this small “dedication” indicated a connection to a much larger story – one I was determined to get the bottom of.

Aquastar S.A. originated in 1958 as a dive gear company aiming to produce water-resistant pieces for skin diving and the growing sport of SCUBA. Their first watch model, introduced in 1960, was the Aquastar 60. This simple skindiver featured a patented stainless steel bidirectional bezel. Despite its obscurity, this model was worn (not so famously) by Don Walsh in 1961 as he descended beyond 10,000 meters into Challenger Deep as part of the two man crew of the submersible Trieste. Aquastar watches were held in high regard among those involved in diving both recreationally and professionally and their watches were sold through Scubapro in the US, while Cressi-Sub and Spirotechnique handled sales internationally.

The Aquastar 63 was a deceptively capable watch for its age. In 1963, this 37mm diver featured an internal dive bezel that could be adjusted with a turn of the crown. Interestingly, the crown did not screw down, yet the watch was rated to an astounding 200 meters, something indicated just below the iconic seastar logo at the bottom of the dial. The case of the Aquastar 63 features a generous amount of stainless steel and sports a relatively long lug-to-lug length. These two features combined to make for a rugged and legible dive watch that were purpose-focused in-period, but in modern context, make for a vintage watch with proportions that remain relevant and stylish.

The dial of the Aquastar 63 features a large internal rotating bezel with silver accented indicators and a lumed triangular pip at the 12 o’clock mark. Generously lumed applied indices are located at 6, 9, and 12. The watch’s date window is asymmetrical, and one of my favorite small details on this watch is that the numerals of the date wheel are similarly asymmetrical. It is a deliberate choice that shows how much thought went into the design of this watch. The dial itself has a gray sunburst effect that looks right at home under the domed acrylic crystal. Although an unusual dial finish for a dive watch, it does make for a unique and captivating watch viewing experience. That said, handsome aesthetics are one thing, but it was that little inscription that really drew me in to this watch.

The inscription on this particular Aquastar 63’s caseback might leave you with more questions than answers. I wish I had the full scoop, but the research on this piece is a work in progress.

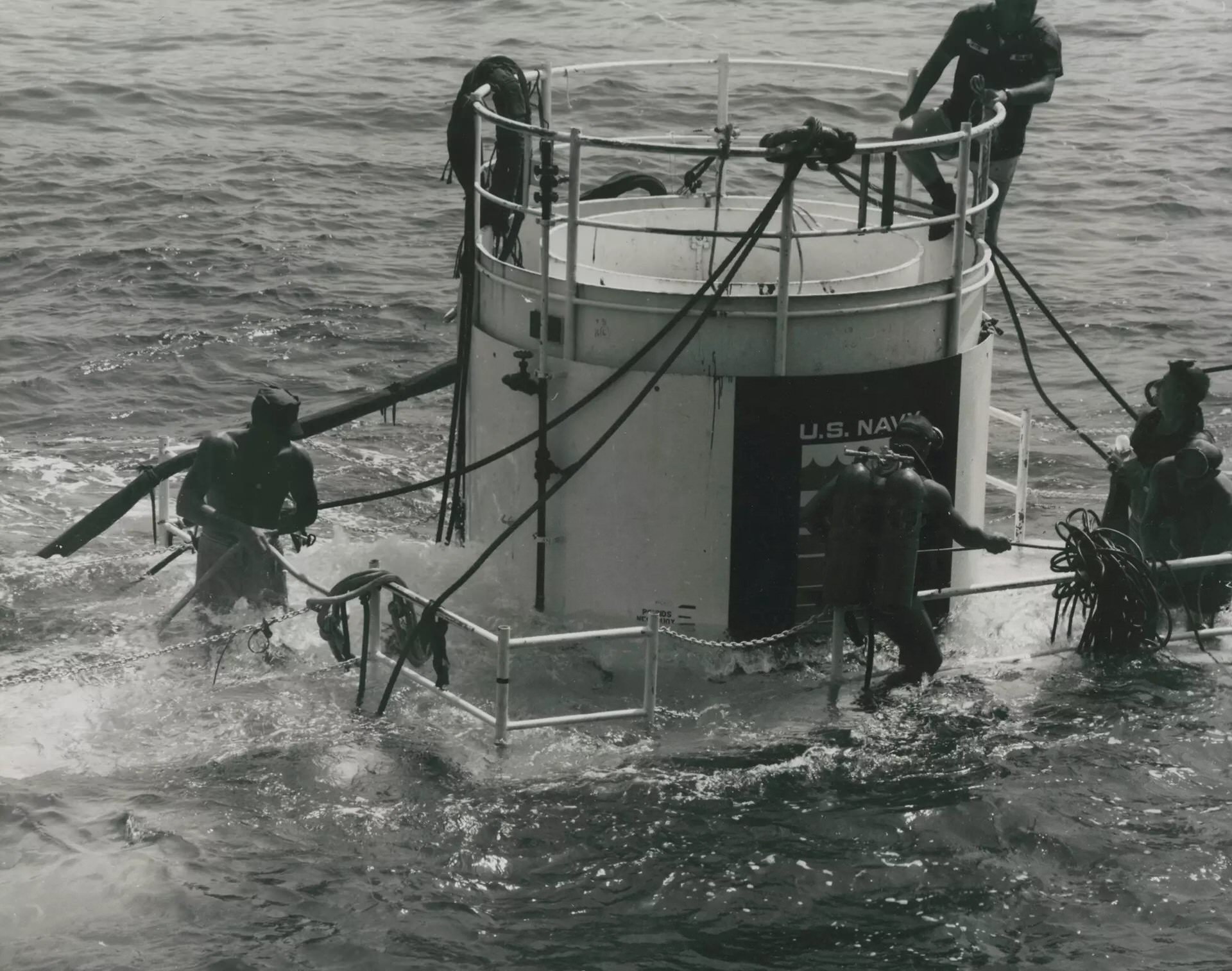

The caseback inscription reads “From Smitty to John.” Obviously the first question is who were these men? Luckily the caseback also reads “SEALAB II.” Could it be the SEALAB II? As in the US Navy-funded SEALAB II where 28 aquanauts lived for 15 days on the ocean floor off the coast of La Jolla, California in 1965?!

Most students of dive horology know that the aquanauts of SEALAB II were issued Rolex Submariners, so how exactly did an Aquastar 63 end up down there (if this watch did, indeed, end up down there)?

It is important to highlight the significance of SEALAB and determine if there is any documented connection between this historic naval undersea program and Aquastar watches. Fortunately, the nature of SEALAB (being a government program), means that there is some chance of archival information existing which could shed some light on this watch’s involvement in the program.

The SEALAB program was funded and implemented by the US Navy, with assistance from the Scripps Institute of Oceanography. The primary purpose of the initiative was to investigate the practicality of long term dwelling beneath the sea in a special mixture of gasses. This program was the beginning of what is now known as saturation diving. SEALAB was a program that advanced the science of diving and in-turn advanced the technology of wristwatches by leading to the creation of the helium escape valve, which is a useless feature to anyone not doing a saturation dive, but an undeniably remarkable innovation in its own right.

No two cases in watch history are quite the same. I’ve had experience researching a late-1970s Antarctic Seiko watch with a unique dial, but this Aquastar required a different approach. The obvious first move here was to ask the seller about the watch’s history. Discouragingly, the seller told me that he had no recollection of the place or year where the watch was purchased – let alone who sold it to him.

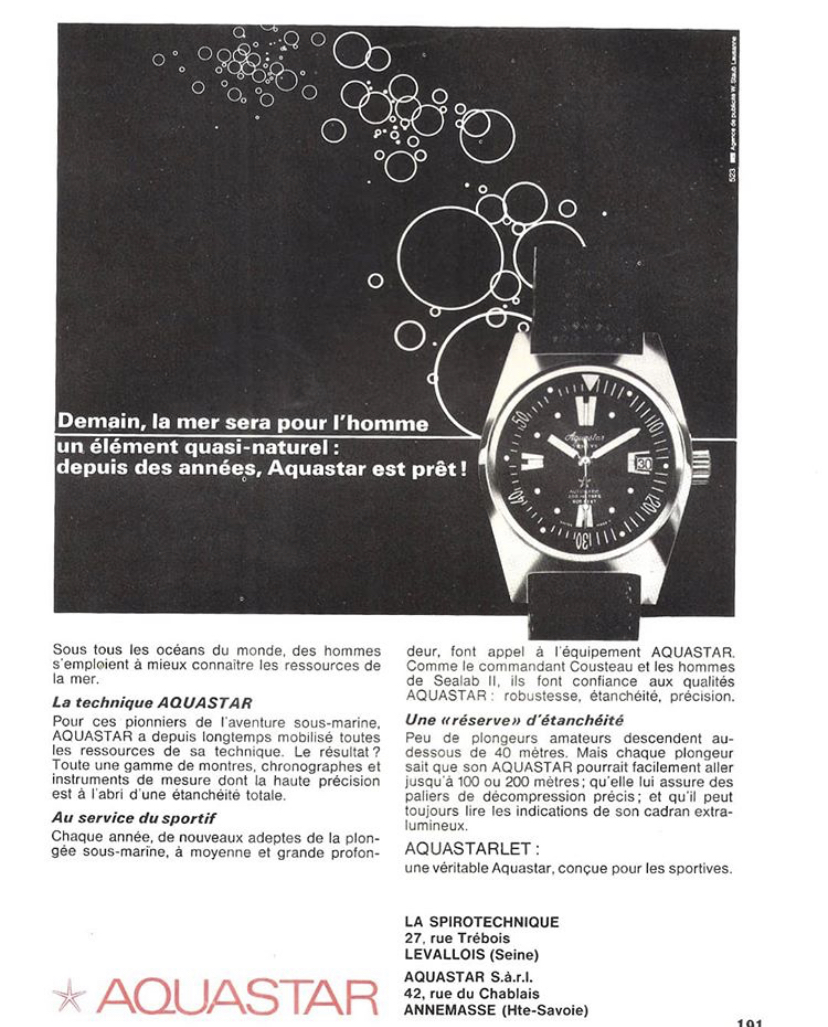

The next logical step for me was to dig into Aquastar history, so I went about researching their ads and seeking out old forum posts to see if there was any documented connection between this company and SEALAB. The forums yielded little information, but vintage Aquastar advertisements did provide some clue as to the connection.

Many of the ads from the late 1960s mentioned that Aquastar watches were used in SEALAB II, Pre-Continent (or Conshelf, a Cousteau endeavor), or simply Man-in-the-Sea programs. Unfortunately, these ads could be little more than clever marketing as they made no mention of the models used in SEALAB, or even if it was Aquastar watches that were used, rather than their popular watchband thermometers.

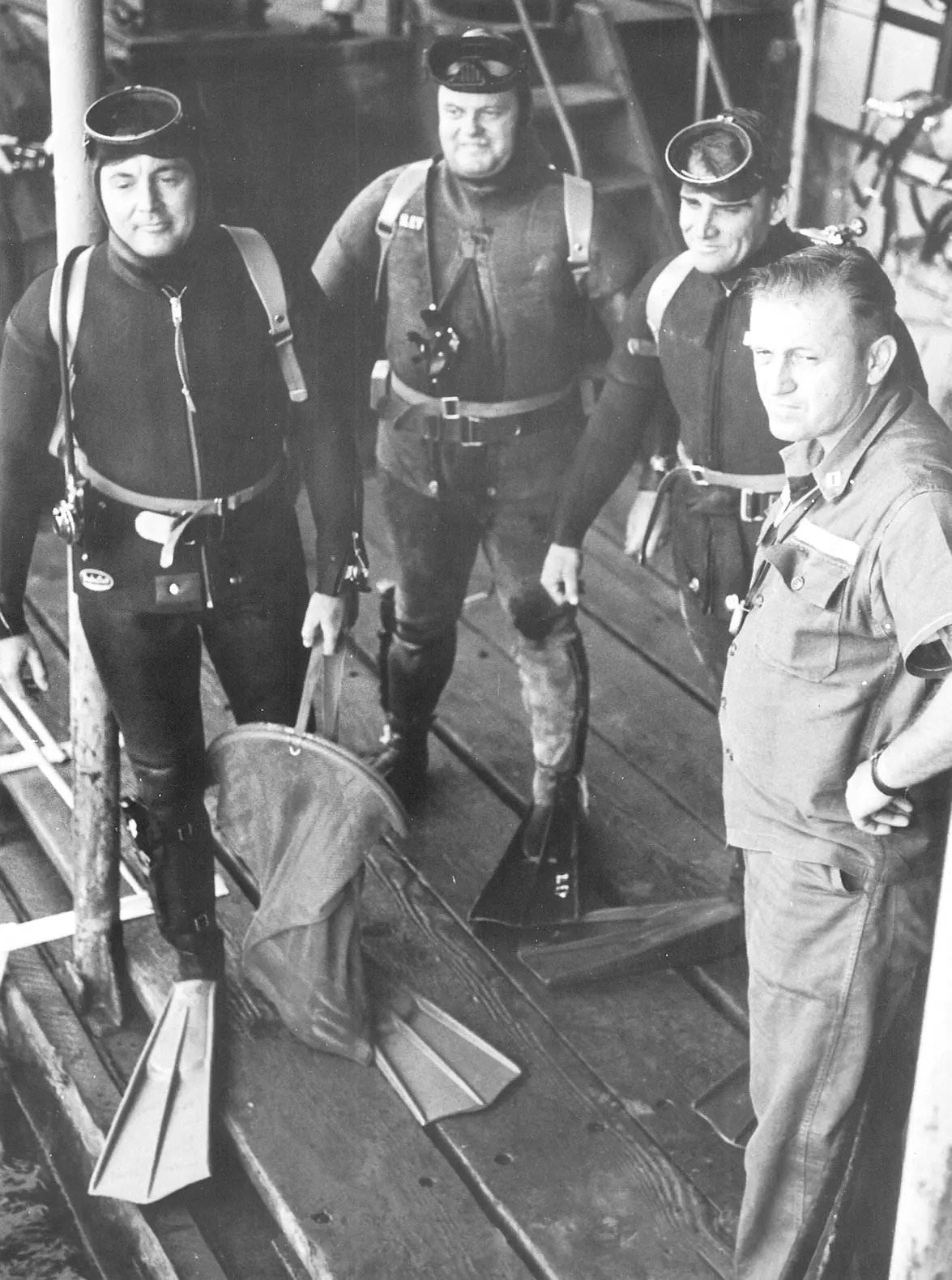

While the discovery of multiple advertisements mentioning this endeavor provided a glimmer of hope, it was clear to me that I would need to start digging into this connection at the source. It was then that I reached out to the US Naval Undersea Museum in Keyport, Washington and became fast-friends with one of the curators. After discussing my watch, and what I hoped to find, she provided me with a veritable treasure trove of image scans, rosters and official documents from the SEALAB archives. I have no doubt that the information provided by the museum was integral to any of my success in learning more about this watch.

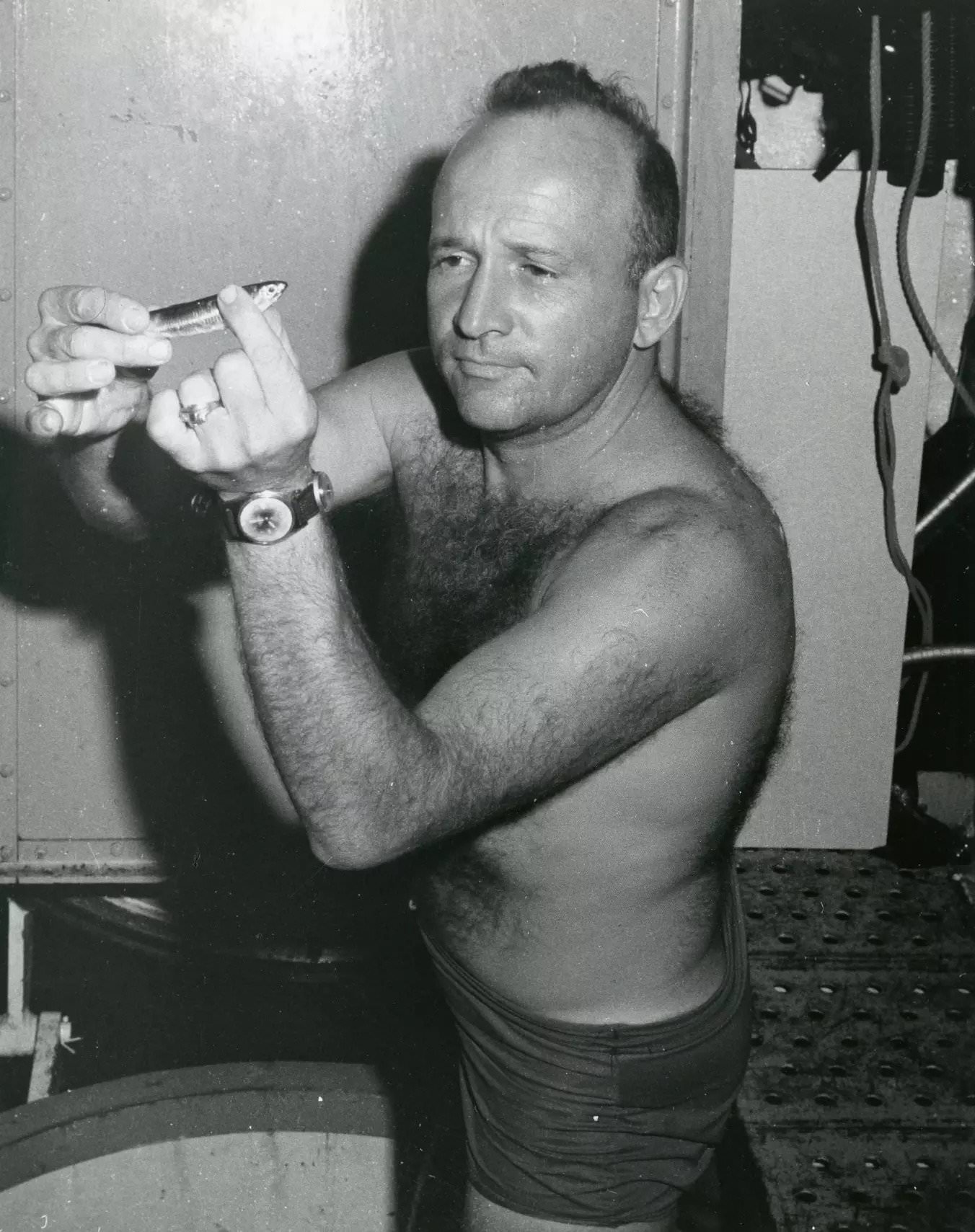

The majority of the photographs from the museum were donated by the children of Jay Skidmore, who was an aquanaut and photographer on team one of SEALAB II. This team was led by former astronaut and real life action hero, Scott Carpenter. There were over one-hundred high quality photo scans, and I searched the wrist of each person in each photo for any sign of Aquastar involvement. Predictably, I counted a multitude of Rolex Submariners, already well-documented as a watch used by SEALAB Aquanauts. I noticed some Blancpain Fifty Fathoms, a few Zodiac Seawolfs (Seawolves?), and even the odd Enicar.

Eventually, deep within my newfound archive of scans, I came across a photo of aquanaut Fred Johler, who was holding an anchovy near the access port of SEALAB II. The watch crystal in the photo appears foggy, but the watch had the appropriate case shape to match the Aquastar 63! Given the quality of the photographs, I was able to zoom in and further inspect the watch better and I found it clearly had a single crown and inner-rotating bezel – which severely reduced the number of potential models the watch could be. The hands were visible, and seemed to match up to the same shape and size as the hands on my 63 model. There was no doubt in my mind that this aquanaut was wearing an Aquastar 63 while living 200 feet below the surface of the Pacific Ocean during SEALAB II in 1965. Here it is, a verifiable connection between SEALAB and Aquastar!

Armed with the official Navy report for SEALAB II, I decided that it would be pertinent to look for aquanauts named John. Unsurprisingly, there were three of them among the twenty eight total aboard SEALAB II. There was Dr. John Morgan Wells, a research assistant from Scripps. I spoke with a friend of his who explained that he typically went by Morgan rather than John. I also had a hunch that the owner of the watch was most likely to be a member of the Navy, which helped to rule out Wells as a likely candidate. Why did I think that John was a Navy man and not a civilian? Navy men love their nicknames and according to the caseback inscription, the watch was a gift from a “Smitty.”

The other two Johns aboard SEALAB II were John Reaves – a USN photographer assigned to team 2 – and John Lyons, an Engineman First Class who was previously assigned to the US Navy Mine Defense Lab in Panama City, Florida. Lyons was on team 3 of the SEALAB II program. Any image I was able to find that contained either of these team members did not clearly display an identifiable wristwatch. However, I have written about the other watches of SEALAB in the past and sifted through hundreds of photos that made it clear to me that each aquanaut likely had a few wristwatches with them, which makes sense to me as the Navy was always sure to plan for the potential failure of any piece of equipment on a high-risk mission.

As if pinpointing one of the most generic first names in the US wasn’t difficult enough, finding out who “Smitty” was seemed like an even more daunting prospect. Naturally, I swept every roster and document I could find for any Aquanaut with the last name Smith. This is all working under the notion that the Aquastar even belonged to an aquanaut in the program, rather than one of the many support divers or surface staff. It turns out, there were many men named John on the rosters, but nobody named Smith served as an aquanaut during SEALAB II. And while the official Navy report is extremely thorough, it does not go into the minutia of every employee involved in the program. In SEALAB, the aquanauts were understandably the stars of the show.

With what little information I was provided by the Navy Undersea Museum, I turned back to internet sleuthing. Considering that SEALAB II took place in 1965 and many of the aquanauts were seasoned divers well into their 30s at the time, many of them are no longer with us today. Such is the case for John Wells, Lyons and Reaves. In fact, tracking down any living aquanaut proved challenging! I was, however, able to find an email address for Richard Blackburn. He was on team 2 of SEALAB II and also on the first and only team to dive in SEALAB III. I reached out to him explaining the research I was doing and without much hope of hearing back.

Within a couple of days, Blackburn had responded and shed some light onto the identities of both “Smitty” and John. He indicated that the watch likely belonged to John Reaves, who was a friend and teammate of his during and beyond SEALAB II and III. Reaves and Blackburn even worked together as commercial divers and treasure salvors for Real Eight Company after leaving the US Navy. They remained in touch for many years.

As for the mysterious “Smitty,” Blackburn indicated that it had to have been from a man named W.H. “Horrible” Smith, who went by “Smitty”. He was the Diving Officer for SEALAB II and a salvage diver of some renown. Confusingly, he preferred going by “Smitty,” though many referred to him as “Horrible.” I suppose, given the options, I would prefer “Smitty” as well. Thanks to the kindness and sharp memory of Blackburn, I now had a name to research.It didn’t take me long to discover that W.H. Smith had passed away in the early 1980s, which meant I would have no way of talking directly to either individual who possessed the watch originally. However, I found a reference to “Horrible” Smith in the book Mud, Muscle, and Miracles: Marine Salvage in the United States Navy by Charles Bartholomew and William Milwee. The footnote on page 248 reads:

Although much remains unknown about Smitty, I continued my search for more information. Ideally, I had hoped to find reference to him as “Smitty” by someone involved in SEALAB. As fate would have it, the US Naval Undersea Museum sent me a full scan of Dr. George F. Bond’s journal that he took for the duration of SEALAB II. This was a firsthand and personal account of the events that took place from his point of view. For reference, Dr. Bond – also known as Papa Topside – was a pioneer in the field of diving, and is now credited as the ‘father of saturation diving.’ It was Bond who sought to explore the concept of mixed gasses and long-term dwelling upon the ocean floor. With help from others, he gathered the data and evidence necessary to gain approval for the SEALAB program and the subsequent SEALAB II and III. It is no understatement to say that SEALAB would not have existed without Dr. Bond, and the experiment itself is representative of his life’s work.

Having a digitized copy of Bond’s journal in itself was terrific. He is an adept and skillful writer with a vocabulary that far exceeds my own. I knew that his daily musings were not likely to mention details as specific as brands of watches. Instead, I scoured the pages for mention of “Smitty” or “Horrible.” Towards the end of his journal, I was excited to find just that.

My working theory at this point is that W.H. “Horrible” Smith had this watch engraved for John Reaves. The reason for the gift? I doubt I will ever be able to truly determine the answer. Nevertheless, this watch was almost certainly involved in the SEALAB II program, be it topside or 200ft below the surface. Perhaps both. I am hopeful that more photos of Reaves or Smitty will show up in the future, but for the moment I am just honored to own a piece of horological and dive history.

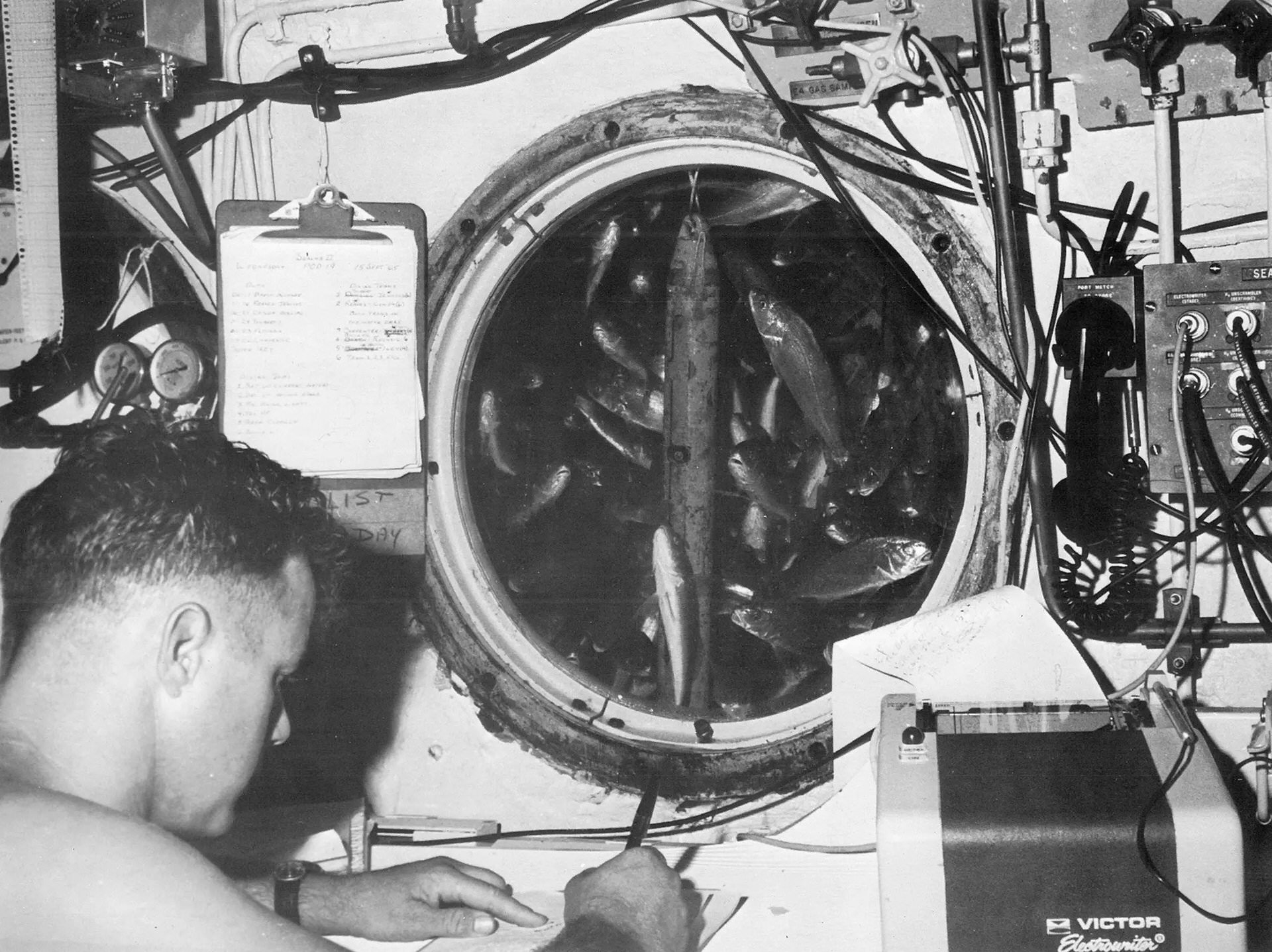

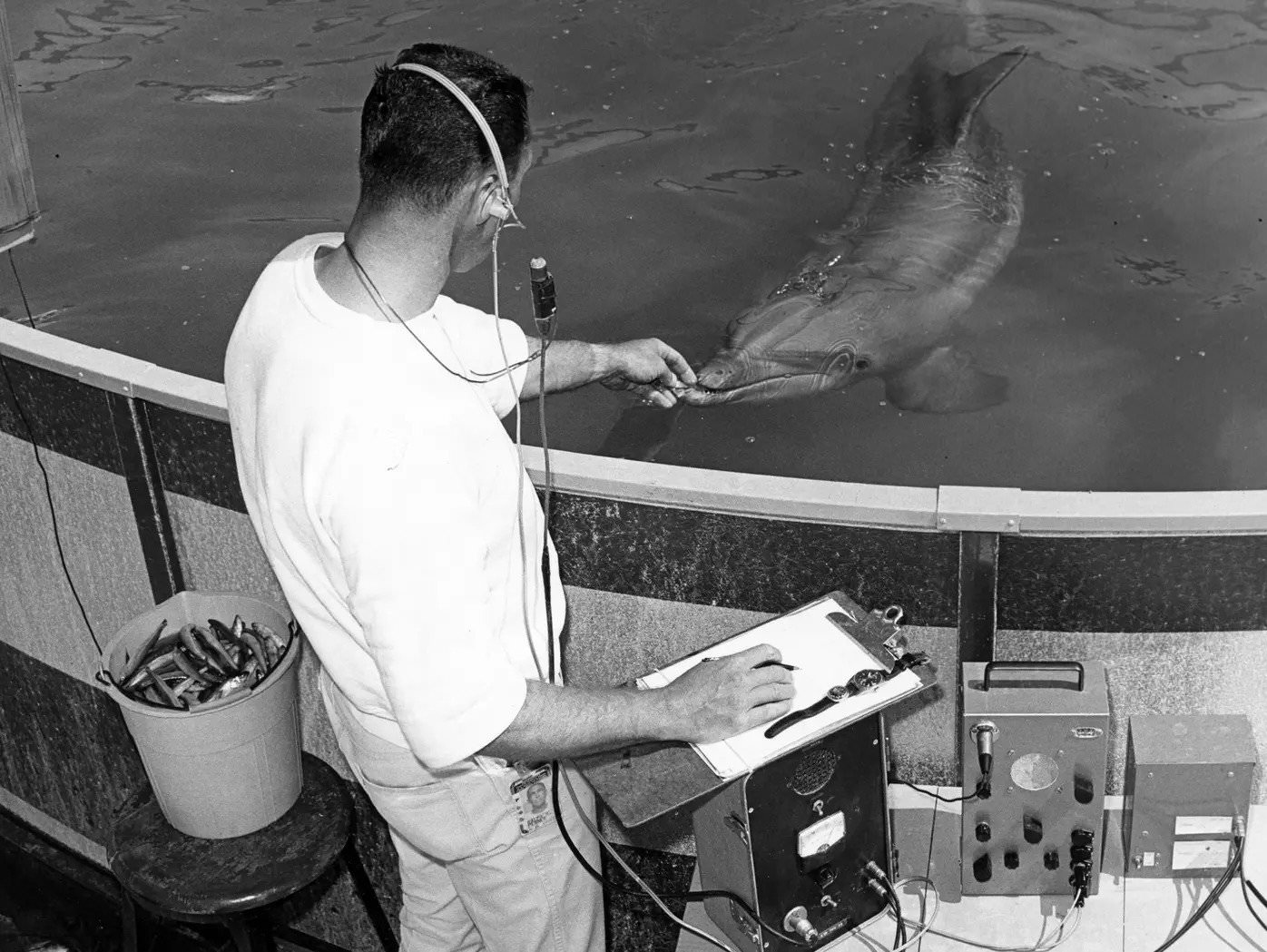

During the process of my research, I came across another Aquastar 63. If you look closely at the scientist’s clipboard, you will see it. Prior to SEALAB II, the US Navy started the marine mammal program. The focus of the program was to train marine mammals to assist with duties ranging from locating lost divers to shark protection and marine salvage. The most impressive of these undersea soldiers was “Tuffy” (short for tough guy) a Tursiops Truncatus or Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin. He possessed a renegade attitude and wore his battle-scars prominently below his dorsal fin. Speculation is that his noticeable scarring was from life-or-death battles with sharks. Needless to say, Tuffy triumphed. I can only imagine the sharks were not so lucky.

With proper training, Tuffy displayed an intellect and skillset far beyond those of his comrades. Tuffy made his debut to the world during SEALAB II, working closely with aquanauts John Reaves and Kenneth Conda, who had undergone special training at Point Mugu. Tuffy delivered mail and supplies, and showed that he was capable of locating divers upon the sounding of a distress beacon. In many ways, Tuffy is the forgotten aquanaut. This pale gray torpedo of professionalism and military service helped to pave the way for the US Navy Marine Mammal Program, which exists to this day.

Originally published via The Wristorian, used with permission.

Check out 'Reference Tracks' our Spotify playlist. We’ll take you through what’s been spinning on the black circle at the C + T offices.

Never miss a watch. Get push notifications for new items and content as well as exclusive access to app only product launches.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates and exclusive offers