To call the helium escape valve useless is hardly accurate as the mechanism itself is actually incredibly useful and represents a massive innovation in watchmaking. However, the real-world conditions in which one finds a use for one are so incredibly rare and specialized that most who own watches equipped with helium escape valves will likely never encounter them – even those that are professional scuba divers! And yet, despite all the misinformation and general lack of a need for this highly-specialized feature, helium escape valves receive a fair amount of attention and can be found on a significant percentage of the dive watches in production today.

A helium escape valve (often abbreviated HEV in the industry) is effectively a one-way valve located on the side of a watch that permits trapped helium gas molecules to vacate the case in a controlled manner. They can either be automatic or manually actuated, but their core function remains the same regardless of style or positioning. Although they are typically only found on dive watches, helium escape valves actually have nothing to do with water resistance, and this detail has resulted in much of the confusion that surrounds this highly-specialized dive watch feature.

As strange as it may sound, helium escape valves are not actually used by scuba divers. By definition, scuba diving (as a category) involves the use of a self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (hence the same SCUBA). Saturation diving, however, is the most elite form of commercial diving and is a different skill entirely, one in which divers receive their air supply from the surface and spend weeks at a time living in dry pressurized chambers and breathing specialized gas mixtures.

In fact, the only time that a helium escape valve will ever actually perform its intended function is during the decompression stage of a saturation dive, and this takes place inside a completely dry environment. Additionally, the purge of the trapped helium gas molecules occurs so quickly that even if you were looking directly at your helium escape valve as it performed its intended function, you wouldn’t be able to see it do anything at all.

For most people, understanding the concept of a helium escape valve ultimately only leads to more questions. Where do the trapped helium molecules come from? How do they get into a watch? Wouldn’t unscrewing the crown during decompression basically do the same thing? Why do saturation divers need one in the first place?

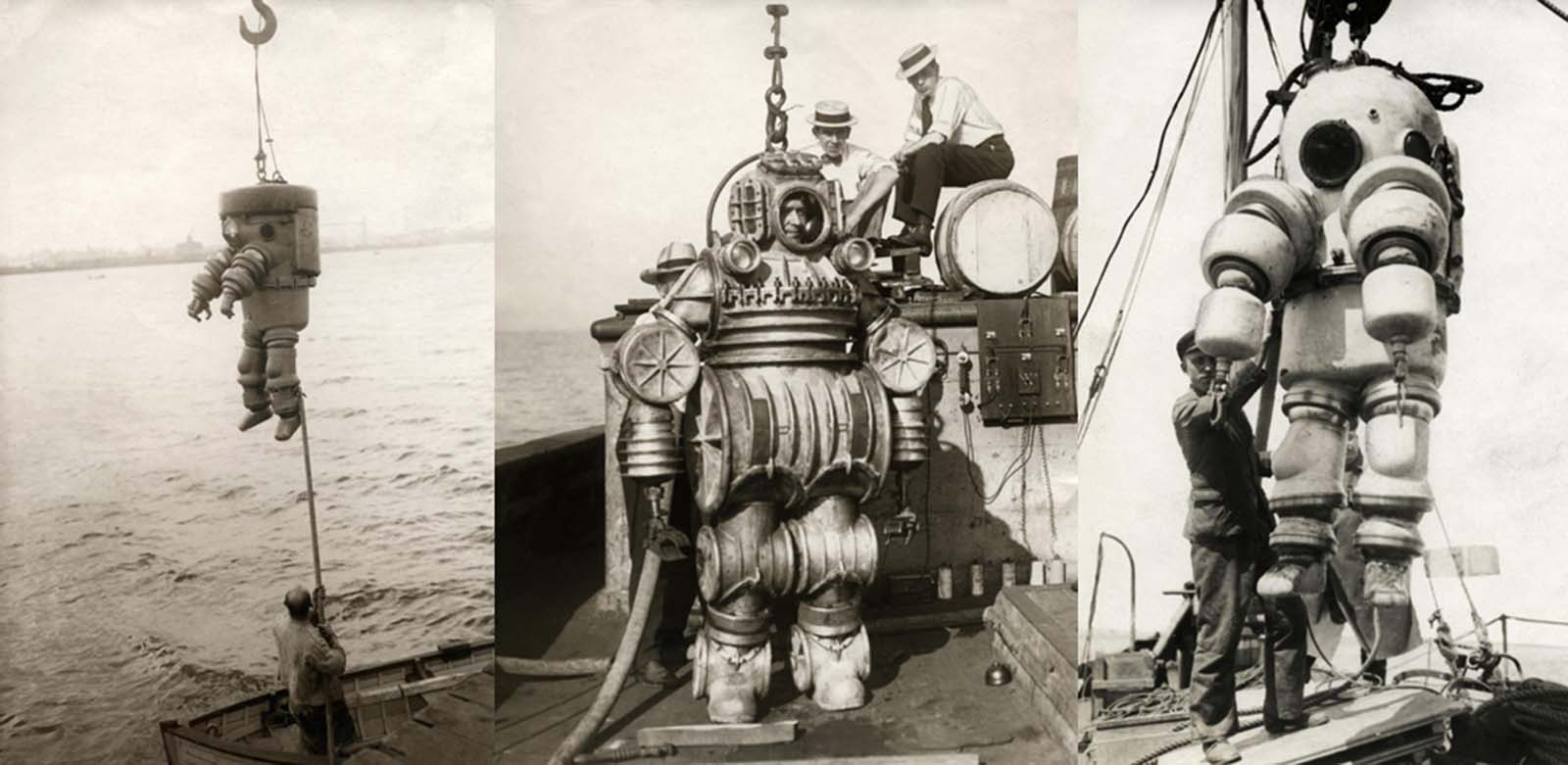

Humans have always wanted to explore the underwater world, but our ability to do so has largely been limited by the technology and equipment available to us. Primitive systems for allowing people to breathe underwater date back to the late 1870s, but it was not until the 1950s that numerous advancements in the field opened the doors to scuba diving as we know it today.

By the 1960s, diving really hit its stride and the idea of humans being able to live in underwater habitats had fully rooted itself in people’s minds. In 1962, Robert Sténuit spent over 24 hours at a depth of 200 feet in a steel cylinder during the Man-in-the-Sea project, becoming the first official aquanaut. That same year, the first Conshelf project launched, which is considered to be the first real underwater habitat. Spearheaded by Jacques-Yves Cousteau, the project consisted of two divers spending a full week at a depth of 33 feet.

Photo: Cousteau.org

Photo: Cousteau.org  Photo: Cousteau.org

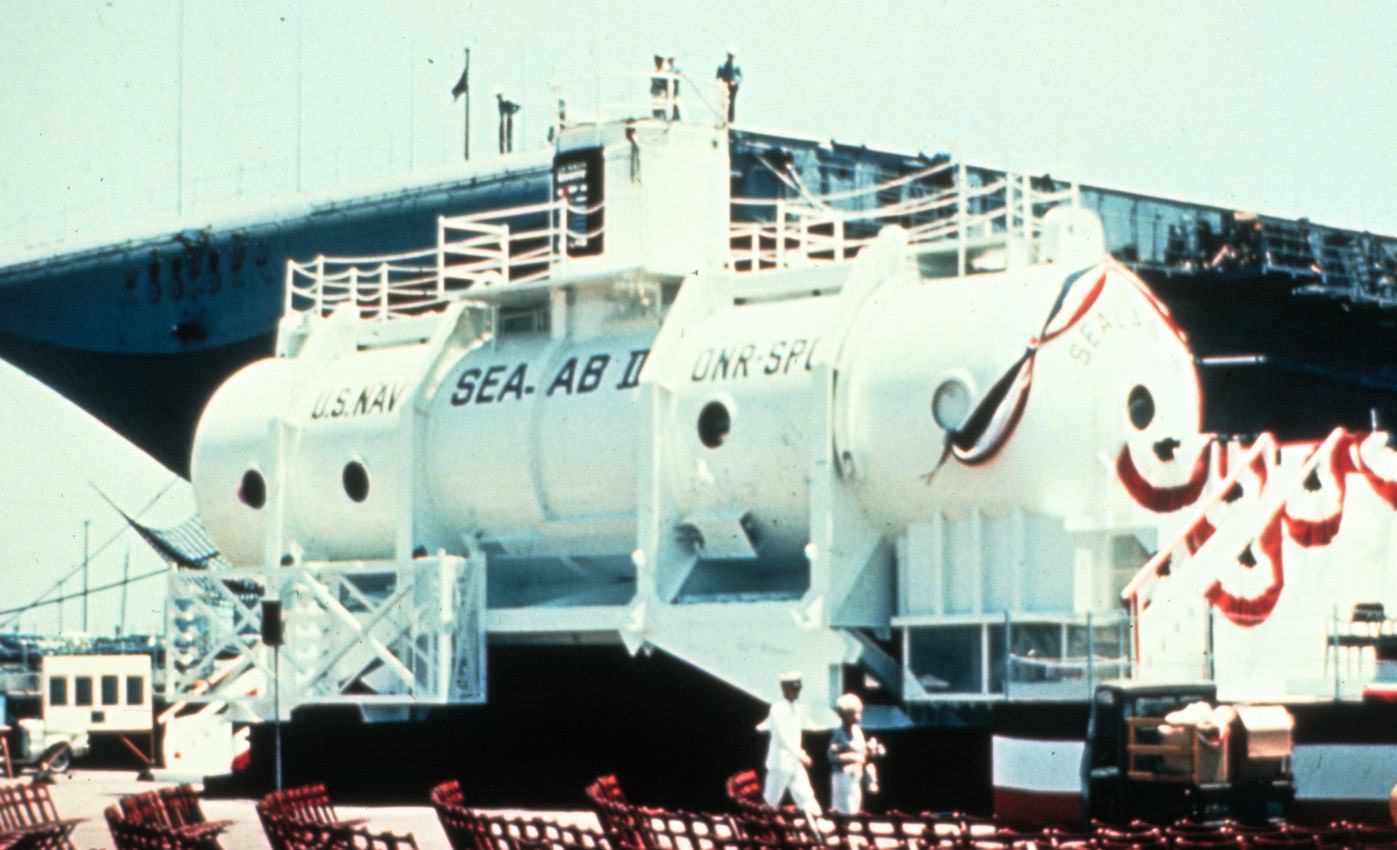

Photo: Cousteau.org When the United States Navy got involved in saturation diving, underwater habitats were seen on an entirely new scale. By the time SEALAB II launched in 1965, the habitat itself was nearly twice the size of the one used for the first SEALAB mission. Additionally, it was placed at a depth of 205 feet and continuously occupied by three different teams of divers for a total duration of a month and a half. SEALAB II even featured a trained bottlenose dolphin named Tuffy that came from the United States Navy Marine Mammal Program with the intended purpose of transporting supplies and rescuing SEALAB divers in distress.

However, one fundamental issue with living underwater is that nitrogen (which makes up approximately 78% of the regular air we breathe) has an anesthetic effect at high pressures and this results in nitrogen narcosis, which comes with similar effects to drunkenness. As you can imagine, any altered state is hardly ideal when you are deep below the surface of the ocean where even the slightest mistake can have fatal consequences, and particularly bad for scientists conducting research.

To get around the issue of nitrogen narcosis, helium is used in place of nitrogen for the gas mixtures during saturation diving. Although this completely solves the issue of nitrogen narcosis and makes things exponentially safer for divers, it does create an entirely new issue for the divers’ watches. Helium molecules are incredibly small and after spending multiple weeks in a highly-pressurized, helium-rich environment, the tiny molecules inevitably work their way past a watch’s gaskets and into the case.

This does not create any problems for the watch as long as it stays under pressure, but it can cause big problems during the decompression stage. According to Boyle’s Law, volume increases as pressure decreases. Therefore, as the air pressure returns to normal inside the decompression chamber, the volume of the trapped helium gas molecules inside the watch expands. Since dive watches are primarily designed to withstand external pressures, a strong internal pressure can damage components and sometimes even force crystals to pop clear off their watches.

The issues surrounding trapped helium molecules first started to arise during the mid-1960s with the rise of saturation diving, and the watch industry’s top manufacturers were quick to adapt. Rolex and Doxa were two of the very first brands to find effective solutions for contending with trapped helium, and the core concept behind their initial helium escape valve designs are still being used by watch manufacturers today.

In 1967, Rolex was first to the party and launched the Sea-Dweller, which featured the industry’s very first helium escape valve. At the time of its debut, the watch was considered a highly-specialized professional diving tool, and it was originally only made available to commercial diving companies such as COMEX, rather than being sold to members of the general public. In fact, it was actually the Doxa Conquistador from 1969 that holds the claim of being the first commercially-available dive watch fitted with a helium escape valve.

There were other solutions to the helium problem, however. Other manufacturers – such as Omega and Seiko – were able to successfully make their watch cases completely impenetrable to helium. Rather than finding a way of contending with trapped helium, this approach simply did a better job of avoiding the issue altogether. This may sound like a far superior and more elegant approach, but this method is actually less efficient than simply creating a way for the trapped helium molecules to safely exit the case.

When saturation diving, a watch is under great pressure for the entire duration of the dive. This means that it is subjected to the same crushing pressures both inside the dry chamber and when outside and actually in the water. If for any reason the crown needs to be unscrewed to either wind the watch or adjust the time/date, helium will immediately enter the case and it will then need to be let out during the decompression stage.

Therefore, this also means that unscrewing the winding crown can actually be used as a method for letting trapped helium molecules out of a watch during decompression. Prior to the advent of the helium escape valve, this was more-or-less the only way for divers to let trapped helium exit the case but it is far from an ideal approach. In truth, you don’t really want to unscrew the winding crown at all when saturation diving, despite the fact that the entire decompression stage is carried out in a completely dry environment.

As mentioned, the dry chamber in which the saturation divers live in during an assignment is highly pressurized and this means that the ambient pressures within it will force dust, dirt, and grime inside the case when you unscrew the winding crown. Saturation divers’ watches often require more frequent service specifically due to this unique issue. For this reason, the one-way design of a helium escape valve offers a far superior solution as it enables the trapped helium molecules to exit the case without also creating an opportunity for dirt and debris to enter it.

While so many of the innovative features and complications found on our favorite watches do not really serve necessary functions in our daily lives, the truth is that these exact same features breathe life into a timepiece and make it something special that truly resonates with us on a personal level. The vast majority of people do not need a mechanical split-seconds chronograph, nor do they need a minute repeater, and they certainly do not need a helium escape valve, yet we love these technical little wonders!

Each feature and complication was developed for a specific use and their very existence is still the core reason so many of us find watches interesting in the first place. As enthusiasts, we love watches because of what they can do, not because of what they actually do for us. Whether we are talking about a perpetual calendar that automatically adjusts for the different number of days in each month or a dive watch that can travel down to some unimaginable depth, we appreciate these watches because of their abilities. We rationalize chronographs by saying that we use them to time things, and we justify massive depth ratings by saying that we sometimes go swimming. However, when it comes to helium escape valves, we can’t justify why we need them; we just love them.

Check out 'Reference Tracks' our Spotify playlist. We’ll take you through what’s been spinning on the black circle at the C + T offices.

Never miss a watch. Get push notifications for new items and content as well as exclusive access to app only product launches.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates and exclusive offers