When the DVD first came out, Hustwit – who had become a de facto film producer and distributor through his publishing work – founded Plexifilm with Sean Anderson, who was the former head of DVD Production at the Criterion Collection. Plexifilm was one of the first companies to release culturally relevant indie films and docs on DVD and offered an alternative to the typical big studio fare that was being pumped out in the media’s early days.

The common theme throughout all of the career shifts and hat-swapping Hustwit has experienced has been trying to create the things he wished were already available; simply seeking to answer the question “Why hasn’t someone made this yet?” over-and-over. That desire ultimately led to a career as an acclaimed filmmaker and director with a focus on niche documentaries that explore the design world and its visionaries.

Films like Helvetica (2007) examined the role of typography and graphic design in visual culture, and Objectified (2009) looked closer at design as a discipline and the way we engage with objects in our daily lives. These docs not only became unlikely hits, but are considered watershed works that legitimized films for design nerds as a genre and helped deliver the conversation about design from the industry clubhouse and subculture to the mainstream. Hustwit’s films have often championed and looked at the criminally unheralded creatives responsible for great design – people like German industrial design godhead Dieter Rams, whose life and work with Braun Hustwit covered in his 2018 documentary Rams, which also featured a soundtrack by the legendary sonic innovator Brian Eno (who Hustwit is currently making a film about).

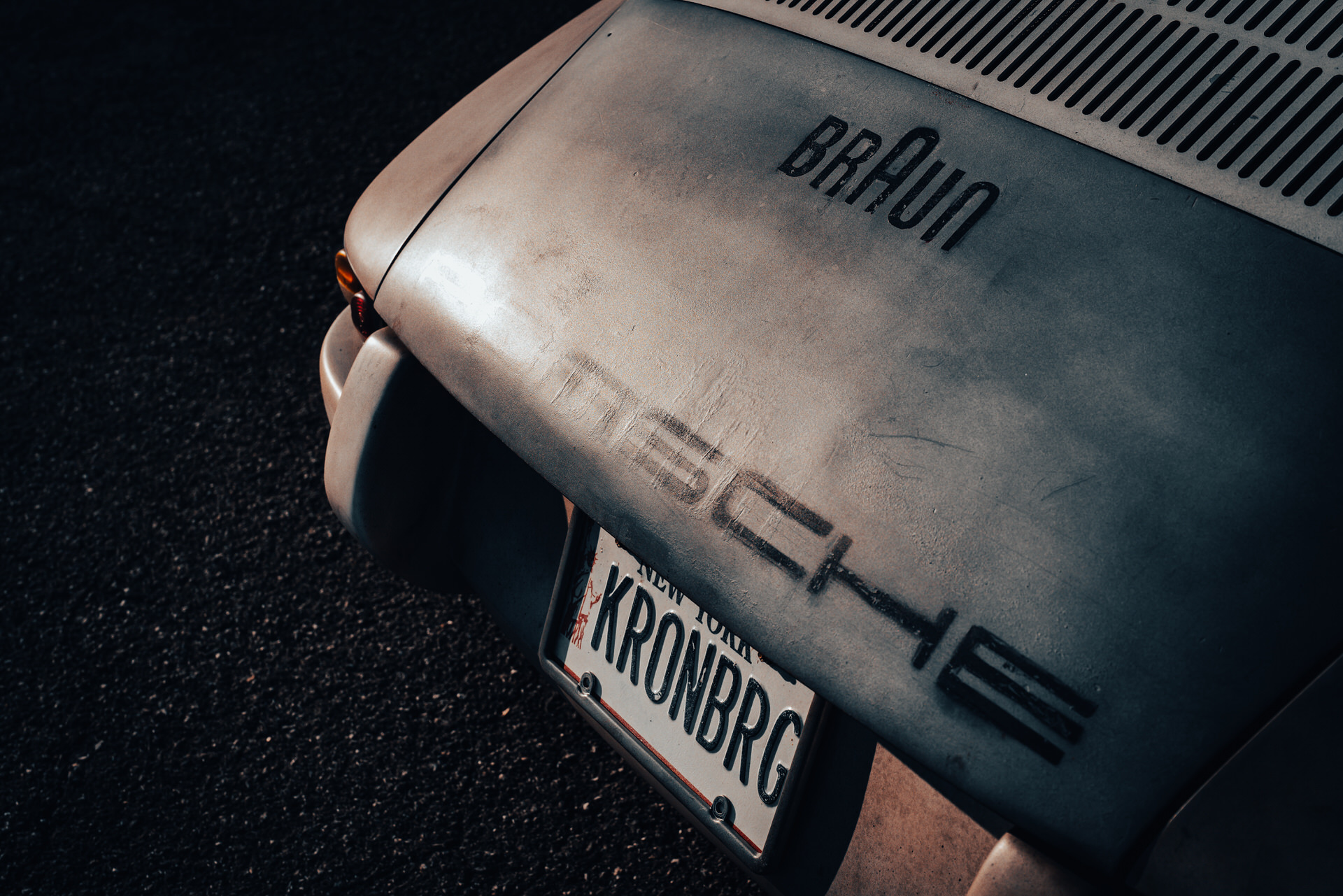

Hustwit’s most recent project takes his fascination with Rams and the pieces he designed for Braun and applies it in an unexpected and brilliantly refreshing way to a project car: A back-dated and hot-rodded Porsche 911. As with all of Hustwit’s pursuits, the Kronberg 911 – named for the town in Germany which Braun is based – started with a question: “What if Dieter Rams, a lifelong Porsche 911 devotee, had decided to go racing in the early ‘70s and Braun had sponsored the car? And what if that car had been rediscovered as a barn-find?”

The idea for the Kronberg 911 proved to be an intoxicating mix of playful and plausible that Hustwit found himself obsessing over and with the help of New Jersey’s ROCS Motorsports’ Richard Gonçalves, he set about making the idea a reality. The pair collaborated closely on the design and details of the car for over a year and the results are simply sublime. While there is no shortage of back-dated, modified, and hot-rodded vintage 911s on the road these days, the Kronberg 911’s conceptual background and beautiful execution give the build a personality that’s undeniably more interesting than the lion’s share of flared and high-polish resto-mods chasing Singer glory these days. It’s a charm that’s already earned the car an appearance at the East Coast’s halo car show, The Bridge.

The 911, which started life as an ‘87 Carrera model, sports an artfully applied patina that’s meant to look like a race car that was campaigned for years, stored, and found untouched. The car has been given a flared look, an aggressive stance, was substantially weight-relieved, and boasts a 3.4L engine out back. It also incorporates no small sum of Braun design easter eggs – things like a deck lid that cleverly mimic the speaker grill design of the Braun L1 from the ‘50s – but do so in a cohesive looking way that comes together without seeming forced or overbearing. It’s an approach to building a 911 that transcends Porsche culture to become an art piece in itself, but is a car any 911 enthusiast should appreciate.

Unsurprisingly, a man that’s explored the design world as thoroughly and granularly as Hustwit has would also have a few choice wristwatches in his collection. Hustwit’s small, but focused collection features pieces that also trace his interests in design: Versatility, elevated minimalism, and functionality.

In the following interview, Gary Hustwit sits down with the C + T Journal and gives us an insider’s look at the Kronberg 911, takes us into his world as a creative, an inspirational do-it-yourself devotee, a design nerd, and a slightly reluctant a watch collector.

You’re a multi-hyphenate that’s led a lot of lives in creative spaces. How do you primarily identify yourself these days?

I’m a filmmaker primarily, but I still do the stuff that I want to do in different media – whether it’s music or publishing books or film. It still all comes back to music for me because when I was in college, all my friends were in bands and I got into the DIY scene in the ‘80s in California and there’s a direct throughline from that aesthetic and that idea of doing it ourselves in everything I’ve done since then.

I played guitar (I still play guitar), but I was never quite as good as my friends were, so I was always kind of like ‘I’m like the band manager, or the concert promoter. Or do you guys wanna put out a record? Let’s start a label and figure it out.’ I was really coming at music from the angle of enabling my friends’ creative projects and coming up with stupid companies and ways to make things happen for them.

You did a stint in the late ‘80s at Greg Ginn of Black Flag’s legendary punk label SST, right?

Yeah. I had already worked helping my friends’ bands release records and I had put together this book called Releasing an Independent Record, which was a really basic DIY guide to putting out an independent release. It was pre-internet and there was no way to find stuff like ‘What’s the college radio station in Rapid City, South Dakota?’ So it was a step-by-step guide with all the people you needed to know, all the places you needed to go, all the pressing plants that would do vinyl or CDs or whatever you wanted to make. It walked you through putting out an album. It was really stripped down and it was mostly lists of college radio stations, independent distributors, and independent record stores in every city in the country. All the info that had been traded around by bands in the DIY world, but in a book.

I heard that SST was hiring in ‘89 and I got a job doing distribution for them. There were a couple of high profile indie record distributors who had gone out of business around that time and SST and a lot of other independent labels got screwed. They decided after that that they were going to build their own in-house sales team, which they had already done in the early days of the label and wanted to return to because they had lost so much money through these distro bankruptcies. That job was a really good way to learn how to do grassroots distribution and tour support for bands, and SST was one of my favorite labels and it was amazing getting to work with those records and those bands – but it was also one of the fucking worst places to work ever. Greg Ginn and Chuck Dukowski are obviously great musicians, but terrible at managing a large group of people. They were really paranoid about anybody wasting time and they were really regimented about how you had to talk to other employees. But it was a great place to learn more about the indie record label business.

I left after two years, but I learned so much working there that I did a new version of the Releasing an Independent Record book. By then other people in the indie music world had ideas for other kinds of reference books and they had started getting in touch with me about books on touring and other music subjects, so I started publishing those. Then I started publishing the work of musicians who were also writers. Dave Alvin from the Blasters is also a great poet, so I put out a book of his poetry and all these spoken word, indie LA musicians and writers. That kept growing.

Your main focus now is documentary film, correct?

I suppose so? I had no desire to be a filmmaker whatsoever, but I ended up getting into making documentaries through music. I went from the music world to publishing books about music, to publishing literature, to moving to New York because I was in San Diego publishing books and constantly traveling out here for trade shows and conferences. I moved to New York to take on the publishing industry in ‘98 and I got swept up into this first wave of dot coms, I opened a bookstore called Incommunicado on the Lower East Side. I had been recording all these writers doing spoken word or readings and I had this big audio library of all these writers doing their thing. MP3 was a big thing at that time and I had the idea to do a literary magazine, but in digital audio – kind of like a proto-podcast before there was an iPod or streaming audio. I started a website for that concept in the back of the bookstore and it got really popular really quickly because everyone was looking for MP3s, and we ended up merging with Salon.com, which was like an internet magazine because they wanted to put all their stories with their writers and personalities and the political work they did into digital audio and expand from just being a print magazine. If the dot com 1.0 economic models would’ve held up, that concept would’ve been great, but that first bubble burst quickly and I ultimately ended up leaving Salon.

Around the same time I moved to New York, I got my first DVD player. I wasn’t a diehard film collector before that, but when I got the DVD player, I was really into being able to watch (what we thought was) really high quality video and movies at home. But the selection of titles at that point was all major studio stuff or classic movies – there was no indie label for DVDs. When I left Salon, I was obsessing over the fact that somebody’s going to start an independent label for film and just do all dvd – kind of like a punk-rock Criterion Collection. Finally I decided I was going to start it and I ended up hooking up with a guy named Sean Anderson, who worked at Criterion and was bored and wanted to do something new.

We started this company called Plexifilm and released whatever we felt like. From cool cult movies and early hip-hop documentaries to other music documentaries. I didn’t set out to release only music docs, but the Wilco documentary, I’m Trying to Break Your Heart, was the first thing that kind of came into our world and it did really well. Other music documentaries started coming in and I helped produce like five music music films between 2004 and 2005.

I got obsessed with graphic design when I was publishing books and that had continued through releasing DVDs. It was all about the packaging design and I had become a design geek. In 2005, I realized there were no documentaries about graphic design. I’d been following that world and reading design magazines with amazing people creating typefaces and doing graphic design, but there was no documentary about it. That birthed the idea for Helvetica. It was just ‘Why isn’t there a movie about fonts? I really want to watch that movie.’ I thought I could probably make it myself having seen the process so many times, so I got a camera and just went out and did it. I already had the idea for the film in my head and I could sort of watch it inside my brain. The idea for something like that is the hard part – the concept. The rest of it, going from point A to point B, is like just one step in front of the other. You can plod forward with the process once the idea is in place.

I still think there’s a huge need for more documentaries about design, different areas of design, individual designers, and movements within it. I still have a few that are in the very early stages of production, but I’m still kind of shocked that there isn’t more happening in that space. Design is such a huge subject and it impacts our daily lives on so many levels, and it’s such a global thing, that I would expect there to be dozens of design documentaries coming out every month.

Why do you think it lives in the shadows? I think there’s been an awakening in the last couple years, especially through social media, where average people are getting interested in the role design plays in our world, but it’s still a subculture.

I think for one, design – as a discipline – has a very hard time describing what it does and justifying its existence as a discipline. It’s very easy for people to understand what fashion design is and even product design, most people understand ‘You’re building these things,’ but design as a whole is a little bit more amorphous, or using design as an approach, or user experience design are less universally understood. For example, I think most people know who Virgil Abloh was and what he did or any other designer that makes clothing or sneakers or objects that are very high profile or luxury goods. Not many people know who designed the hinge on a door; a lot of the stuff we engage with daily is designed in a way that’s very much anonymous, and that’s fine, but there was a ton of engineering and thought and creativity that went into designing all this stuff that we take for granted, and I think most people just do take those things for granted.

As design applies to your world as a car enthusiast, you told me that you had German cars growing up and were a Volkswagen guy as a teen. It’s a very common tale to graduate from Volkswagen teen to Porsche adult. Can you walk us through the path you took and how it ultimately led to the Kronberg 911 project?

I grew up in Southern California, so I was always very much into cars. I had a variety of cars in my teens and early twenties, from a Datsun 280Z to an ‘85 VW Golf GTI – which is the first new car that I ever bought. I also had a ‘67 Volkswagen Microbus, red and white, and that was a beautiful, beautiful thing that I wish I would’ve held onto.

I had friends in high school that had Porsches. One had a 914 and another friend’s dad had a 928, and those cars were just something that 16 year olds obsessed over in California. They were gorgeous machines and something I’d always wanted, but it didn’t really have the means then. Then when I moved to New York in the ‘90s, I just didn’t need a car there and you can’t have that kind of car there on an artist’s salary and lifestyle, but I’ve always been obsessed with Porsche – I didn’t have a car for around 20 years because I was living in the city. A few years ago, I got an Audi A3 to be able to get out of the city easier and go to my girlfriend’s place upstate, and that got me back into cars.

I met Dieter Rams when I made my film Objectified in 2009 and he’s famously a Porsche 911 devotee. Dieter took me for a ride in his 993 and a 911 was something that I had started thinking more about after that ride with Rams. The movie came out and then I had this fantasy idea: What if Braun had sponsored a 911 race car in the early ‘70s? What if Dieter had been involved and contributed some of the design cues to the car? What would it look like if that car had been raced and then found as a barn find? What would that car look like? Like with anything else I’ve done, whether it’s the films or any other project, I have the initial idea and then I obsess over them and all I could think was ‘God, it would be so cool if that thing existed.’

That’s such a brilliant starting point for a 911 build.

Of course it had to be white, because all of the Braun stuff is white, and it had to have very minimal graphics, and there had to be some design touches taken from Braun products, but subtly applied. Things like how Braun did their speaker grills expressed in the grill of the car’s deck lid, and things like. It was all a “what if?” concept.

What’s remarkable to me is that there’s a lot of Braun easter eggs laced into the Kronberg 911’s design, but it’s very cohesive. The layman 911 fan that knows nothing about Braun or Rams could look at it and their takeaway would be that it’s a neat racing-inspired 911 hot-rod, but if you really know Rams’ work, there are so many elements that jump out.

That’s partly because Richard Gonçalves at ROCS has been building race-inspired Porsche builds for 30 years now, and his dad and his cousin raced 911s in the ‘70s in Spain and Portugal. So Rich grew up around these cars and really uses those roots to inspire his builds. The Kronberg car is a combination of my ideas about Braun and Dieter Rams and Rich’s ideas about what makes the optimized vintage Porsche race car.

How’d you meet Rich and the ROCS team?

I was following him on Instagram and just reached out a few years ago. He had seen or heard about some of the films I’d done and we started talking. Rich has a couple of builds that were inspirations for the Kronberg build, and one of them is his car that he calls the Panamericana. It’s a silver 911 that has a Telefunken logo on the hood, so another German radio brand like Braun. That car really drove home the idea that a German radio brand sponsoring a 911 race team was plausible and looked right, so I extrapolated out from there with the other design touches the Kronberg has. Things like bringing some of Braun’s industrial design language into the car’s grills.

Walk us through the car. It started life as an ‘87 911, right?

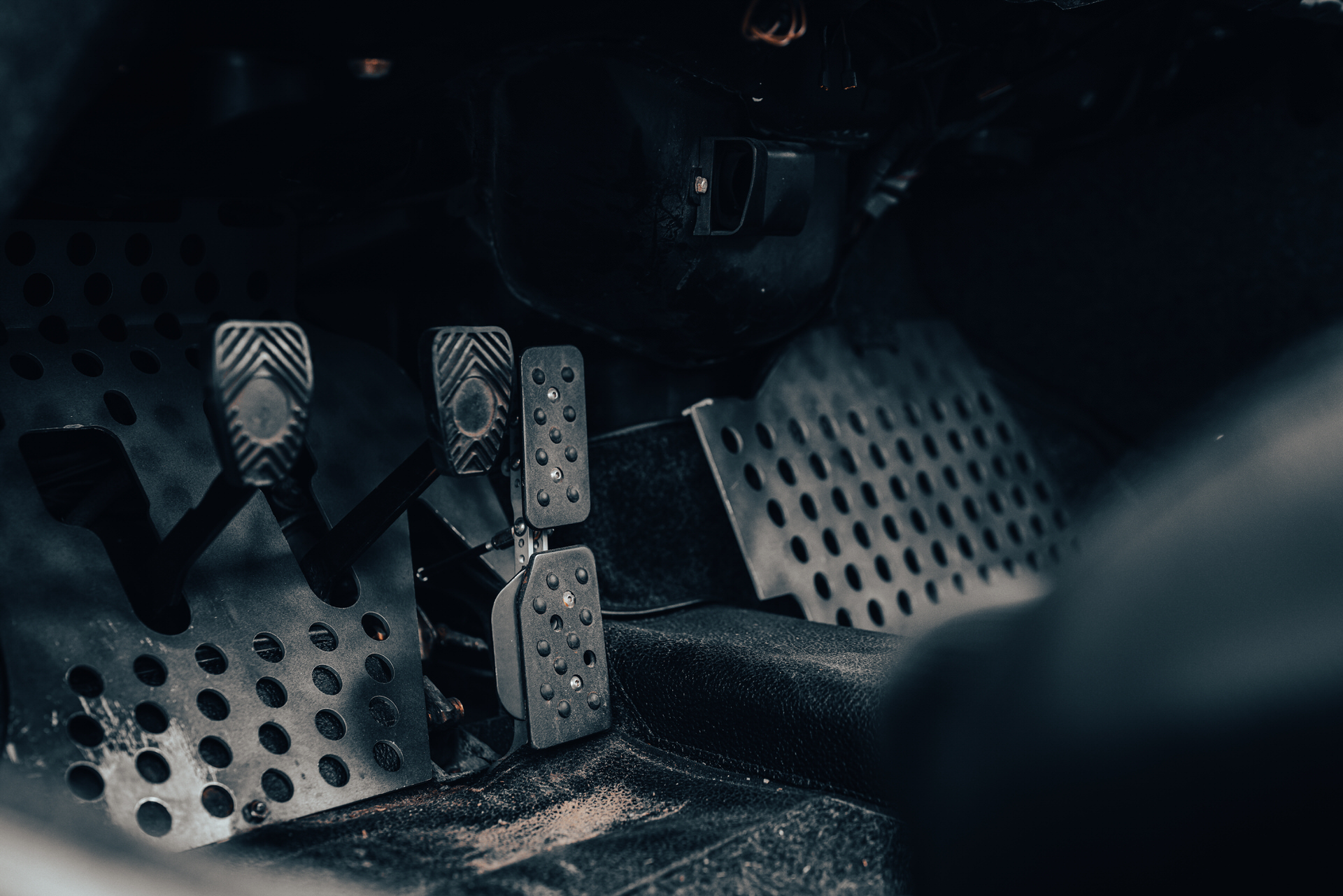

It’s ‘87 Carrera 3.2 with back-dated body panels and an upgraded engine – so it’s got a 3.4L in it now. It’s got a lot of track-capable suspension mods throughout, 16×7” Fuchs wheels up front and 16×9” in the back. Then there’s a lot of custom stuff; the front bumper is a custom thing that Rich made, it’s got a hand-bent aluminum splitter with rivets on the front end.

Originally, Rich had an aviation-inspired vibe that he was going for when he started the build. So things like stripping all the dash covering off to have it in bare metal, then hand shaping the metal around the gauge cluster. Then a lot went into making it a plausible race car, so we did a power window-delete, a sunroof-delete, air conditioning-delete, pulling out all of the interior panels and losing the back seat. So it’s probably 500 lbs lighter than stock and it puts out around 260 horsepower. The car was completed about 6 months ago and took around a year to conceptualize and build. We’ve spent some time dialing it in since completion, but it feels great and the response to the car has been really strong. We did The Bridge show In Bridgehampton with it, which was great.

It’s so much fun to drive and it’s weird, but you just don’t see any air-cooled Porsches on the road in upstate New York these days. It’s so fun driving this car around here, especially on dirt roads and all the mountain highways we have twisting around the Catskills. That’s really a 911’s element. They’re not cars that are going to just disintegrate if it gets below 32 degrees and the beauty of having a car with a patinated finish is it doesn’t matter if it gets dirty or rocks hit it – it makes it look even better. So it’s nice to have a car that I don’t have to be paranoid about using. Honoring the wear is part of the process. If you’re using the object for the use that’s intended for, any wear that comes from that is totally part of its personality.

The way I explain the value of patina to new vintage watch buyers is there’s patina and then there’s damage, and one gives the thing personality and speaks of a life lived, and the other is usually a byproduct of abuse.

But that’s a very fine line, isn’t it? What’s patina and what’s damage? Like most people would see their “tropical” dial’s fade and say “Oh, I’ve got to get this replaced. Can I get a new dial?” But once you get into the minutia of what changed when things from different years were made with different materials or using different finishing techniques and how they all age differently, it becomes really interesting. There’s some people who get that and who are into the wear and the authenticity of that, and there’s plenty of people who just want the thing to look perfect and new.

Speaking of patina, one of my favorite details on the Kronberg 911 is the Heuer Monte Carlo dash timer. Tell me the story of sourcing that piece, which looks perfect in the car.

Well obviously there’s a history of having Heuer timers on the dash of cars like this. I found that particular one online in England and it’s a mil-spec Monte Carlo that had come out of an RAF plane. So it had had 40 plus years of actual use before I got it and that patina actually fits the look of the car perfectly. It almost looks like it’s been relic’d because it has the perfect amount of wear. I remember finding a lot of really nice and clean examples that didn’t really fit the vibe of the car, but this one had a really cool history and that patina, and it also works great.

So after six months of being a vintage 911 driver – which is a very different driving style, especially with the power this car has – what are your takeaways? What are the things that you really enjoy about it? And as an aesthete, what are the details that you look at every day when you engage with the car that you really enjoy?

It’s honestly just really fun to drive, especially in upstate New York. I hadn’t owned a 911 before and getting used to the way it corners and the way it handles at speed has been really, really fun with the roads up here. It’s interesting because I haven’t had a classic car in modern times; I had some of these cars in the ‘80s, but it’s different driving a car like this in 2023. For most people, a car is simply about transportation. Then there are other people who understand the art of driving and the art in the design and the build – and that’s a very fine line. There are people who blow by me in their Toyota Camrys when I’m on the highway, but I could care less about raw speed. It comes back to experiencing this car in a different way and people’s awareness of design. There are people who care about the details and the story and the engineering and the craftsmanship in anything in their lives, and there are some people who just don’t. It’s not a better or worse thing or a criticism, but I definitely do think about this stuff and there are so many factors and layers to the Kronberg 911 that are things that I think about, care about, and geek out on. But at the end of the day, it’s just a fucking blast to drive! I love all the little details that Rich and I worked on for it. That rear deck lid went through probably a dozen iterations before we got the idea to base its design on the ‘50s Braun L1 speakers. Getting those ideas to work well was really rewarding and something I see everytime I get in the car. Everybody asks what year it is and I just pick a different year between ‘67 and ‘73 every time because nobody really knows. Only one person was like “Hmm, I don’t know? The torsion bar placement is off.”

Was Rich a Rams fan before this project?

He knew of Dieter and the Braun stuff, but I got him to go much deeper into the obsession over Rams. It’s interesting, there are a lot of design innovations that Rams and his team at Braun did in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s that continued to reverberate through the world. Even today, you’ve got multiple generations of designers who have been influenced by the minimalist Bauhaus aesthetic. I see it a lot in automobile design, but also in technology and everything that Apple has done. So that design aesthetic and functionally is seen everywhere now. I even see it in Porsche’s modern evolution, too. What was great about this collaboration was to see how Rich processes that aesthetic because it’s a different take. When Rich is doing Porsche builds, he does things that are stripped-down and simple, both visually and in terms of how they function. It’s just another spin on Rams’ aesthetic and ethos.

You’re also a bit of a watch guy, which I think makes sense for any design nerd. What’s in your collection these days?

Well I’ve had this Heuer Monaco for almost 20 years now, and it was just in really nice shape. I like that it’s a little bit more subdued than the alternate color sub-dial variants. I’ve loved Heuer for a long time and I had a nice three sub-dial Camaro before, but this one really is the one for me. I wouldn’t have bought a blue dial “Steve McQueen” Monaco. The understatement of this watch’s gray dial gives it a quietness that the other Monaco variants don’t have, and even though it’s got a lot of complications and presents a lot of technical data, it’s doing it in a very simple way. Is it the iconic version of this watch? No. But this Monaco is that design in its purest form for me, and the squareness and lines of this period of late ‘60s and early ‘70s design really speak to me.

My daily wear alternates between a Rolex Explorer I ref. 114270 and one of the new Tornek-Rayville military dive watch reissues that my friend Bill Yao at MKII watches was behind. The simplicity of the Rolex and the versatility of it makes it the perfect all-around watch in my eyes. I’ve worn that Rolex kayaking and I’ve worn it to a swank dinner party. You can really do both with it. It’s a sports watch, but after they switched to the white gold lume surrounds after the ref. 1016 got phased out, it got a little bit more refined. The 1016 was such a tool watch, but this era of Explorer got a little bit more classed up. It’s still ready for anything and has a rock solid movement, but it’s the perfect all-around watch. I don’t have a dress watch in my collection because this really can work as a dress watch in most cases for me. I’m more interested in simplicity and the functionality of a watch than anything else. As for the Tornek-Rayville, it’s a great daily because of how accurately it captures the spirit and look of the original Torneks, but it’s a really carefree watch to wear and own because of the modern Japanese movement. I think Bill has done a really great job with the brand.

I also have a Rogers Supreme Admiral Automatic watch that was owned by Merle Haggard, and he had given it to a guy named Little Jimmy Dickens. When Jimmy died, they auctioned off all of his stuff, so I got this watch and a Nudie Cohen suit that was also Merle’s, but Jimmy hadn’t altered – which was a good thing because Jimmy was a tiny little guy. It’s a pretty subdued design for a Nudie, but it’s great.

With the Kronberg build done and on the road, I’m curious if you’re still in touch with Dieter and if you’ve gotten any feedback on the build from him?

Yeah, I actually just saw him last July. They had a small reception for his 90th birthday. I sent him some photographs of the car and we talked about it when I was there last summer and he said he thought it was wonderful. I told him I want to bring it over and give him a ride and he goes “Oh, it’s great, it’s great…why does it have to be so dirty?” And that was his main critique, which totally makes sense and I was trying to explain to him that the idea was it’s meant to look like it has wear and has been raced and was stored for years and then found. But Dieter is really not about patina, he’s about clean lines and simplicity, and cleanliness period. Now he’s obsessed with how the wood used on the older Braun radios has yellowed and turned different colors that he thinks are horrible; he wants it to be perfect and perfect forever. But it makes sense; this is a guy that obsessed over every screw they used on that thing and the engineering on the stuff he and his team have made over the years is ridiculous. Just something like the TP1, which is a portable record player, is bonkers. Nothing in 1958 looked like the TP1; everything was tailfins and space age. This is something that’s really stripped down and about functionality. A lot of that had to do with scarcity and limitations on materials in post-World War II Germany. They had to use what they, could and ornamentation didn’t play a role, it was about pure function and making things that were easy to fix and would last you a long time. And Rams really birthed the idea of a modular design language, which didn’t really exist then.

Photos by Monik Geisel

Find Gary Hustwit and the Kronberg 911 on Instagram at @kronberg.racing

Find ROCS Motorsports on Instagram at @rocsmotorsports

Check out 'Reference Tracks' our Spotify playlist. We’ll take you through what’s been spinning on the black circle at the C + T offices.

Never miss a watch. Get push notifications for new items and content as well as exclusive access to app only product launches.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates and exclusive offers