For Oilstainlab’s twin-brother-tandem of Nikita and Iliya Bridan, it took creating something with the sole purpose of tickling their own selfish interests, an attempt to scratch an itch for an unattainable classic – but while sidestepping the pitfalls of building a replica or tribute car. With the Half11, the Bridan twins haven’t just built something wholly authentic and unique – they’ve even crafted a fleshed-out fictional backstory and a wild collection of clever (nearly) believable “historical” materials. It’s a novel concept that delivers the Half11 project from the realm of a cool build to a conceptual art piece; a big game of “what if?” centered around a ridiculously cool (and ridiculously fast) build.

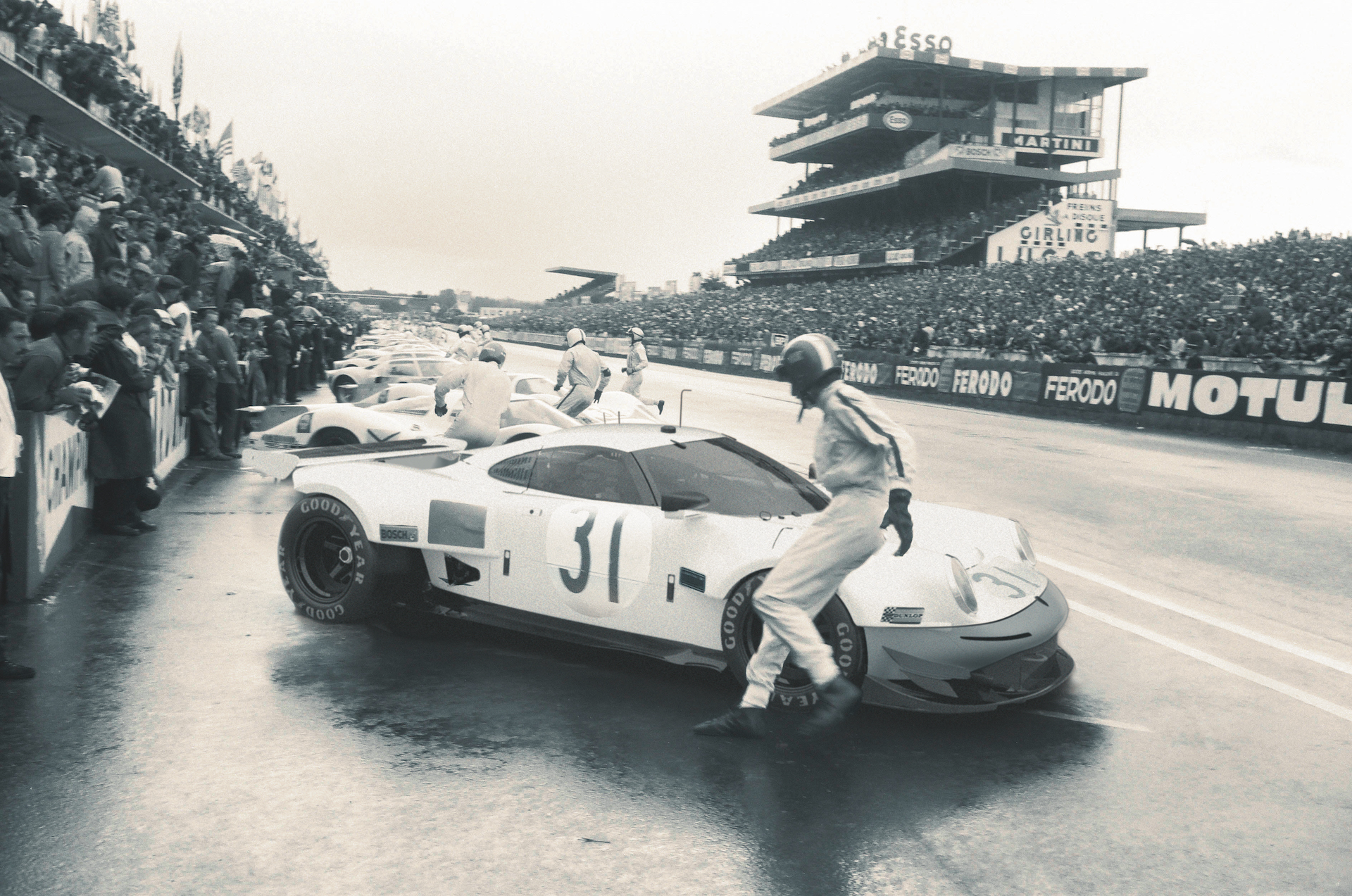

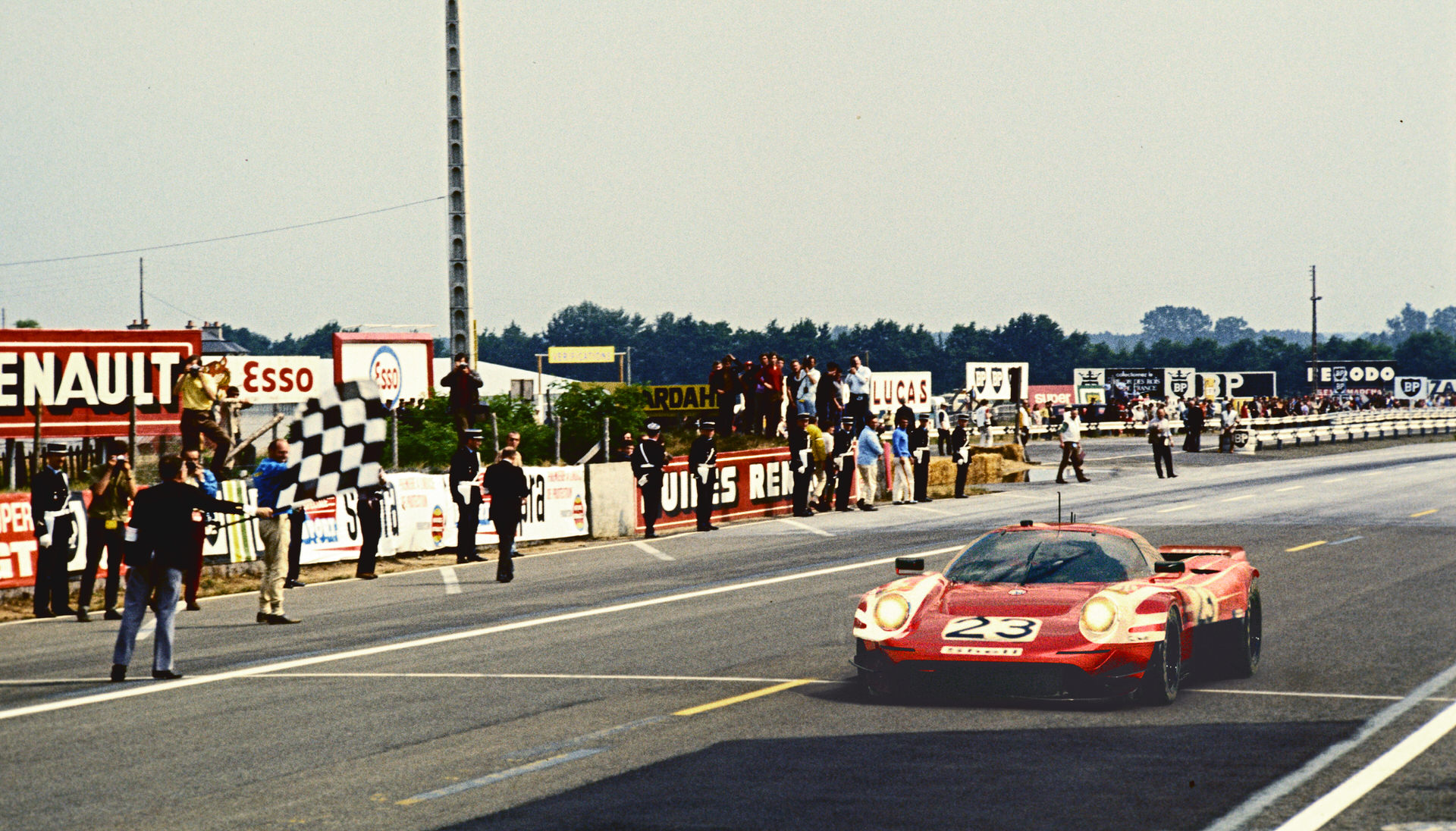

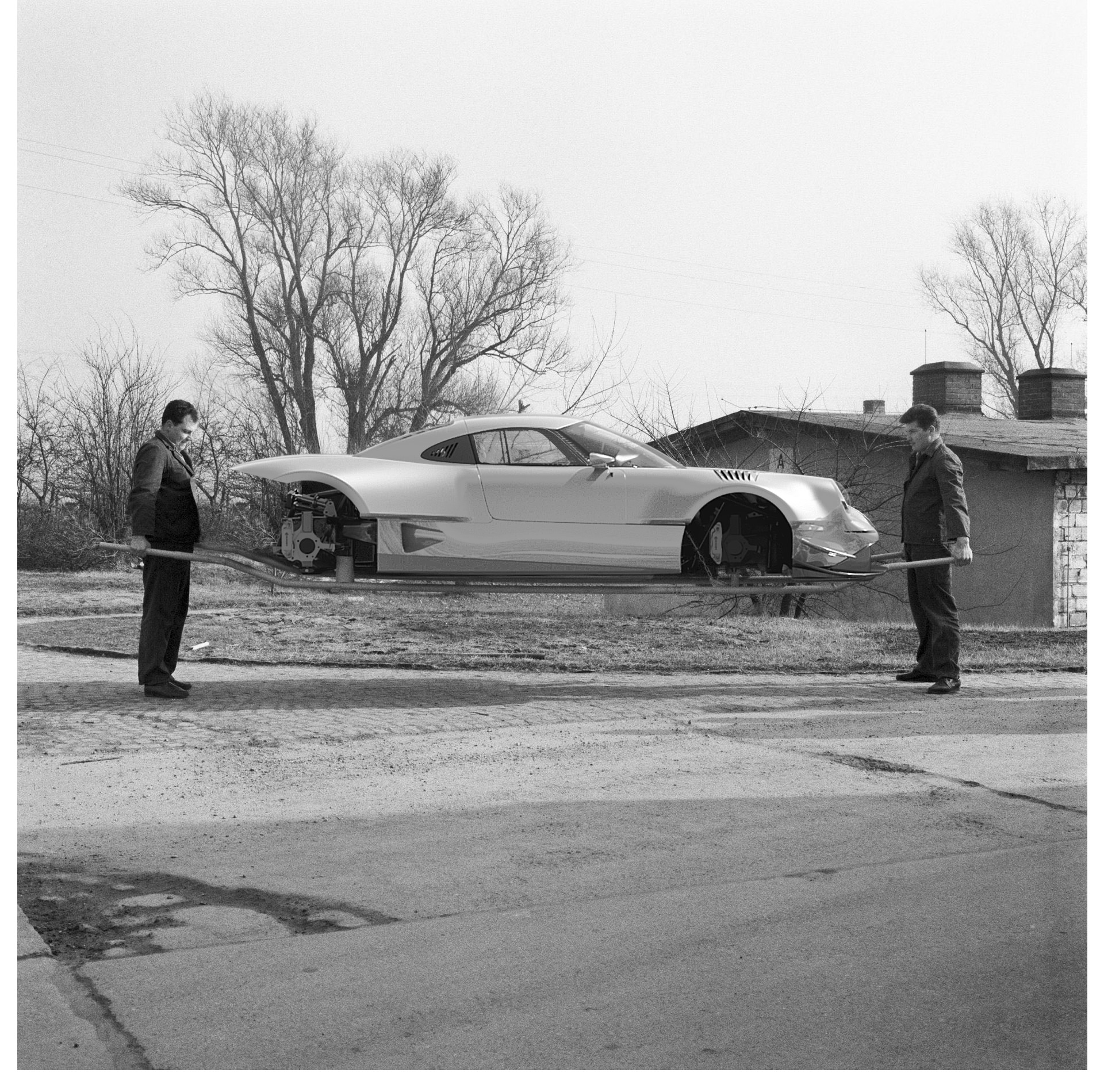

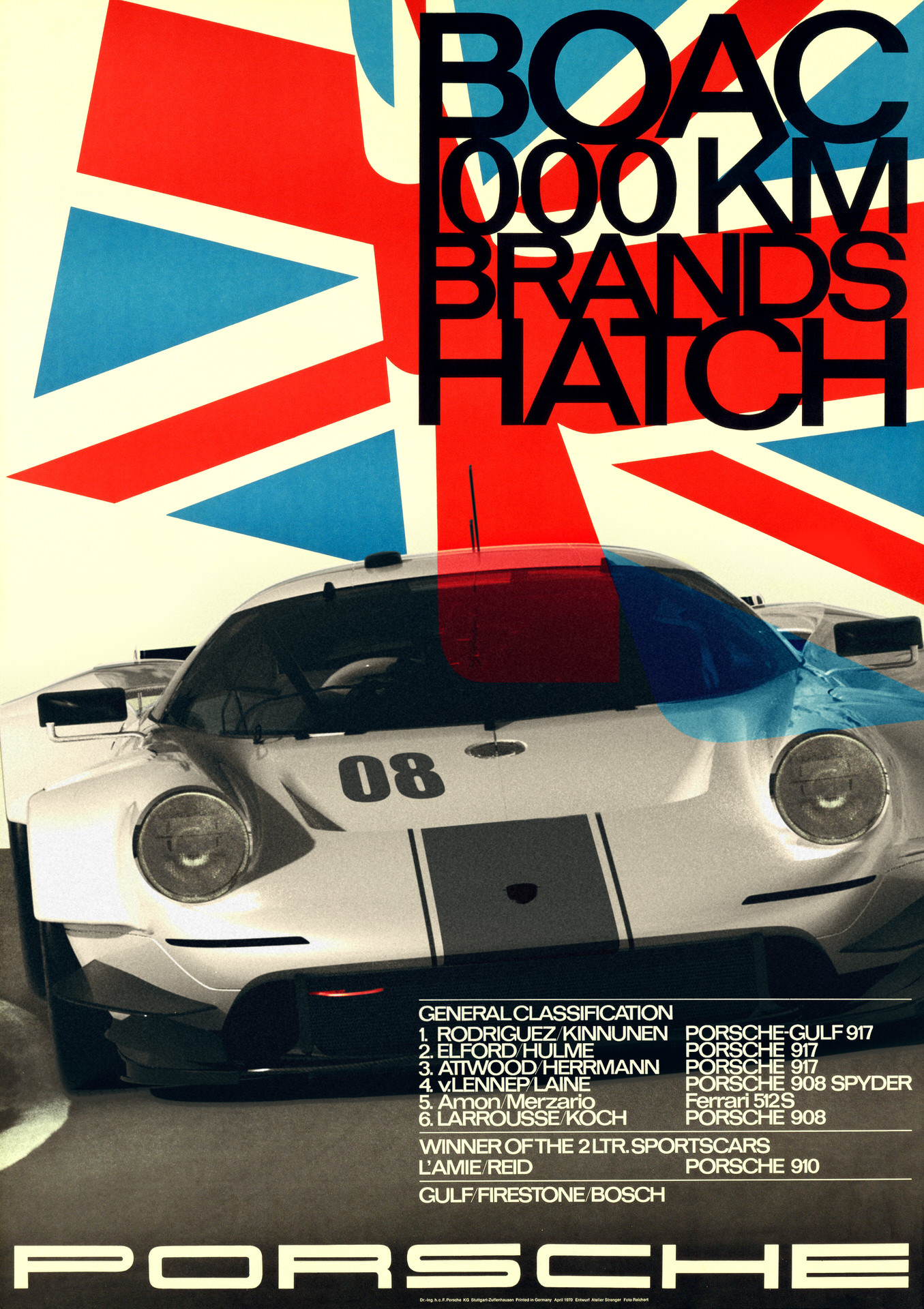

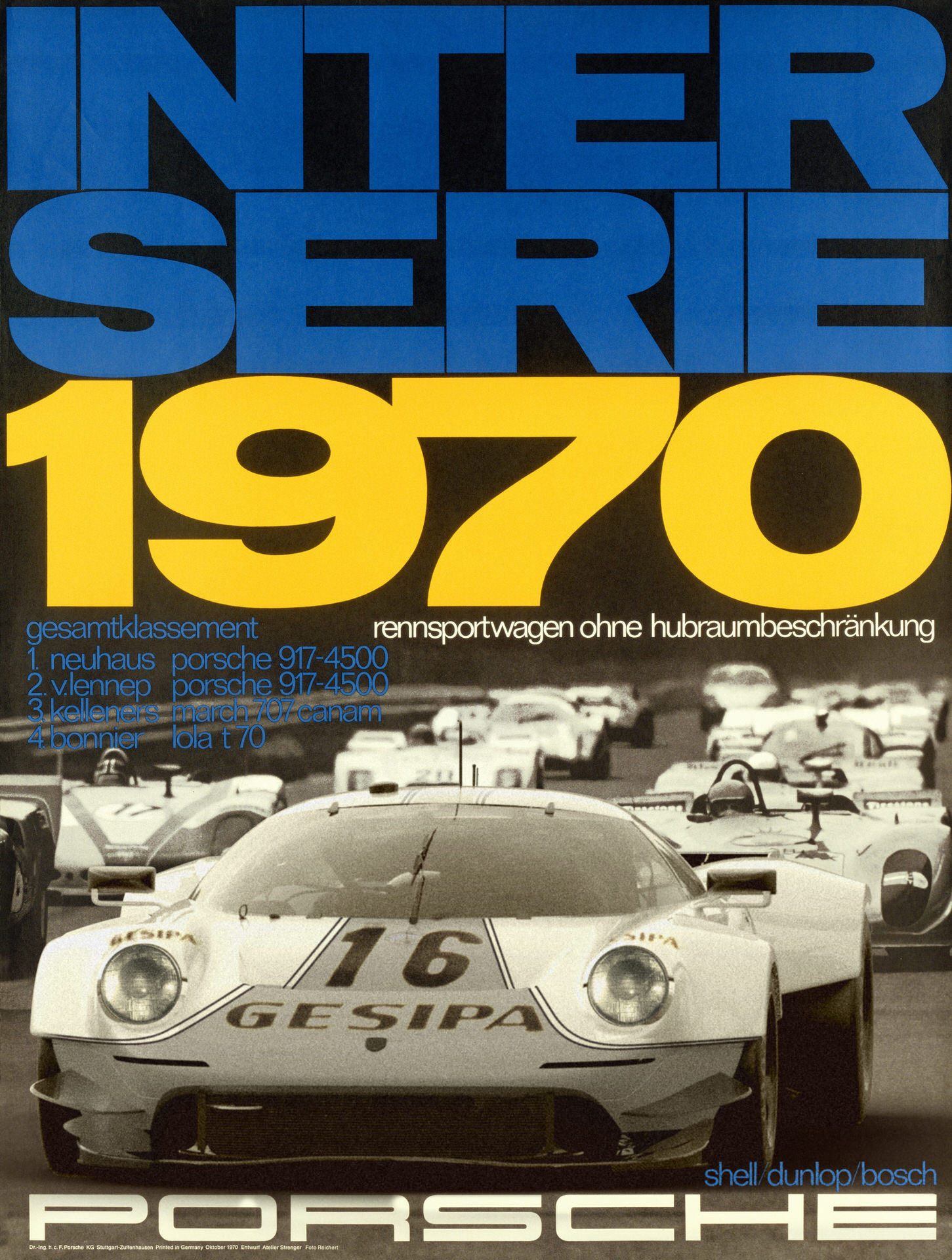

The Half11 is an outrageous-looking, mid-engined, street legal race car that mates the front end tub and aesthetic of a classic Porsche 911 with a spartanly-appointed bespoke tube chassis in an attempt to answer the question “What if Porsche had built a 911-based Le Mans racer that could go toe-to-toe with Ford’s GT40s in the ‘60s?” Something that might race alongside the legendary 917, but allow Porsche to campaign in both the sports car and prototype classes with a single car as Ford did with the GT40. The end result is a painstakingly modified and crafted build that melds the best attributes of that period of prototype racer and sports car. It’s a functional piece of automotive sculpture that has intrigued and confused onlookers for quite some time thanks to the brothers’ brilliant fictitious historical renderings depicting the car competing against the motorsports titans of yesteryear and exceptionally believable digital mockups of the car, but has recently delighted crowds in-the-metal at the Quail – where it was plucked from the parking lot and given the “Car Park Concours de Quailegance” award – and the Bridge – the country’s duo of premier car show events.

Ultimately, the Half11 is a playful, whimsical car that has an element of pure joy baked into its concept that can be easily lost in a vintage car market that’s often restrained by its own costs and precious approach to preserving old cars – even mediocre examples of ‘70s 911s like the Half11’s donor tub came from. For the Bridans, the Half11 was an opportunity to do the very opposite of what they’re tasked with on a daily basis as successful professional auto designers with a combined resume that includes work on futuristic concept cars for no small number of major OEMs, work with Acura’s factory-back IMSA team, and even designing the sadly ill-fated, but incredibly futuristic looking 1400 horsepower Hoonipigasus build that Head Hoonigan and rally wunderkind Ken Block had hoped to challenge Pikes Peak with this year. For a pair that’s constantly asked to design around future trends, building something with the past – even a false past – in mind brought out something incredibly special. And it’s a car that’s taken on a life of its own since wowing the crowds at Car Week and the Bridge. In the following interview, we get the whole story on the glorious Half11 project from Nikita Bridan.

What exactly is the Half11 and how did the project get started?

The Half11 is a pet project that my twin brother Iliya and I did. It started about five years ago when we scored a killer deal on a Porsche 911 tub; we had built a few 911s, but we wanted to do something unique this time and we spent the next 18 months figuring out what the heck we were gonna do with this one to stand out. We just wanted to create something that hadn’t been done before. We had always wanted a Porsche 917, but we realized we’ll probably never be able to afford a 917. So we decided to build this wild thing that looks and feels like it’s from the 1960s – a period of racing that we’re obsessed with – but build it on our own terms. Let’s design our own car, come up with our own backstory for it, and base ourselves in that period.

Both of us are professional car designers, so we normally work on projects that focus on things being released between seven and twenty five years in the future; that’s the typical scope of work that we’re asked to do. We’re always trying to imagine new technologies, what’ll be around in seven years when the car goes on sale, but also what needs to be considered when the car stays on sale for another seven years. So you’re usually trying to anticipate trends and technologies. The Half11 is the opposite of that; it’s us going back in time, creating a false history, and even creating drivers that would’ve driven it and races it competed in. And also trying to be honest to the technologies and the processes and everything that goes into the car so it wouldn’t look like a spaceship if you had transported it back in time.

So we created this whole history for the Half11 and a fake history book with the renderings that people have seen online, and that grounded the design and limited what we could do with the build. It gave us a target and concept, which is a 1960s Le Mans prototype that would’ve raced against the Ford GT40, because at the time, the GT40 was racing in two different classes: sportscar and prototype. Porsche was only racing prototypes then. So we said “Let’s take the 911 and make one that would race against the GT40. What do we need to make that would be able to do that in a plausible way? That’s the Half11.

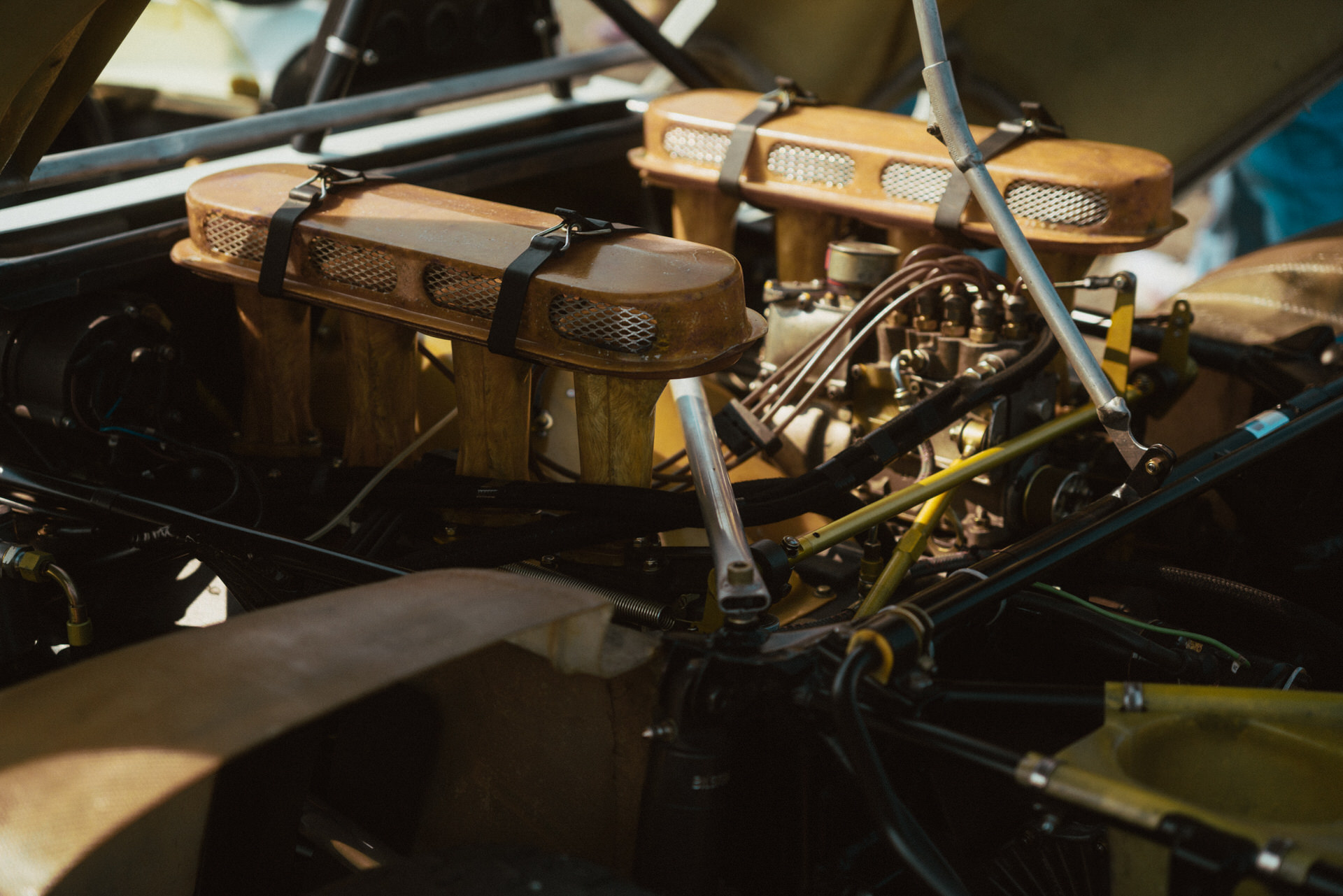

What engine are you actually running in the car?

For the prototype car, we really, really agonized over that. Like I said, we wanted a 917 and the only reason we didn’t build a 917 replica was because we had no idea what engine to put in there that would honor the original car properly. You can’t put a 5.6 because that’s just silly, and any other motor is not worthy of it. And a flat 12, quite frankly, is like $3 million, so that was never going to happen. When we decided to build our own car, we decided we wanted this car to scare us, but we wanted it to work every day and be usable. So we elected to build a crazy LS V8 motor for it which is mated to a 996 GT2 transmission that’s mounted upside down for a mid-engine conversion. The engine is the most controversial part of the car, but for the prototype, it makes a lot of sense because we’re stressing the chassis at its very limits. The car weighs 1,850 lbs wet and it’s got a 650 horsepower motor. The power-to-weight is insane and honestly, any production cars or future client cars probably don’t need this amount of power. It is a terrifying amount of power, but the LS is able to be driven in every condition. The amount of torque that it has makes starting with a triple clutch puck very easy; you can ease into the clutch uphill and it’s not a big deal. The other thing is that we wanted to create a chassis that was able to accommodate both water-cooled and air-cooled engines, so that’s also another reason for the LS and not just dropping in an air-cooled Porsche motor. We wanted to figure out things like if a client wanted to use a new GT3 RS motor, we’d need radiators up front, and how do we manage all the water lines and everything without sacrificing the design itself? So it was a pragmatic decision. And one other thing that makes me feel a little bit better about it Is that the McLaren F-1 named Albert, which was the transmission and seating buck mule, had a Chevy big block V8 in it. That’s just how prototypes are done, and if it’s good enough for the McLaren F-1 mule, it’s good enough for the Half 11. That’s how I justified it. Transmission is a 996 GT2 flipped upside down. So it’s in a mid-end conversion now.

What’s the reaction been like within the Porsche community and with other hot rodders? Are you getting a lot of kickback from people about cutting up a vintage 911 in the context of today’s insane 911 market?

When we first started posting some renderings, of course it was a very extreme statement from the start. We’ve been building the car for about 3 years and I would say the design has matured and it’s had time to age and people have had time to acclimatize themselves to it. So it’s not nearly as polarizing when people see it now as when we first started. The reactions we get nowadays are like 90% positive. Occasionally you’ll hear someone who’s upset that a 911 got cut up, but quite frankly it was not a nice car to start with. It was a solid car, it was a rust-free car, but it wasn’t a particularly desirable 911 – so who cares? The reason we decided to do the project at all was just to stand out. Singer really revolutionized the hot rod 911s in terms of how high-end you could go, how much detailing you could do, how high quality a build could be. Before Singer hit, a hot rod 911 was just slapping a big motor in it and putting some flares on it and then you go racing or canyon carving. Obviously now everyone’s Singer-inspired builds – which is kind of sad because I think Singer does it the best way – but the market that they’ve created has just forced everyone to copy what they do, and no one’s really stepping out of and doing something different.

No one’s ever done what we’ve done, really. Of course the 911 is an icon and it takes balls to cut one in half, but it’s never been a sexy car or really a super aspirational car like a Ferrari or a Lamborghini. It’s never competed on just pure aesthetics. It’s always been a little bit of a logical choice for a sports car; they’re pretty easy to maintain, you can use one every day, you don’t have to drop the engine to do most of the maintenance like in a Ferrari. So 911s attract a very rational buyer for the most part and we wanted to break that completely and create something that’s 911 based, but utterly aspirational in its styling, its proportions, and just the sheer presence of the car. I’ve found that while people like the renderings online, when they see it in person, everyone’s just blown away by it. I think that’s a testament to our entire team, from the metal shaper and the engineers to my brother and I for designing and building it. Everyone says it’s so much better in person, which is cool to hear because cars are physical objects that you need to walk around, you need to sit in, and you need to experience that way, and it’s cool to hear that it translates even better in reality.

The Half11 is making some major waves right now. It was picked out of the parking lot at Monterey Car Week to appear for an award at the Quail and you participated in the Bridge, the two premier car show events in the country. What have those events been like for you?

I mean, it’s been utterly surreal. Starting with Quail, we didn’t think we were going to make it. So we were trying to see if we could make the show, but basically didn’t commit to even attending Car Week. We ended up just trailering the car up and we finished it just in time, and then my friend gave me a parking pass for the show. He was like “You guys just go park the car there and see what happens.” So we parked the car there that morning and then went back to Laguna Seca and got a call that we won an award. It was absolutely mental. So that started this whole whirlwind of attention.

We were talking with the Bridge folks for a few months before Car Week, but again had no plans to attend until about a week prior to the show and then everything came together. The Bridge is such a cool event and watching it from the West Coast, it’s become this kind of mythical thing. I’m sure for the East Coast, Monterey Car Week is very mythical, but from the West Coast, the Bridge is like the premier show. I was always like “One day, I want to be there.” I feel the same way about Goodwood. But it has just been wild, and it’s been wild to drive the car on the street now that it’s street legal. I can’t describe the last couple weeks because it doesn’t feel real in any way, shape or form. What we hoped we’d be doing five years ago when we started this project is coming true and it still doesn’t feel real.

I was unsure for months if it was a real car or just a rendering. I know you guys got that a lot before these major events.

We kind of kept a little quiet on social media about the status of the car before Car Week, other than posting the alternate history images. It’s like Bigfoot, you know? When people see it, the reactions are “Did I just see it? Is it actually real? Is that the Half11? Are there more?” It’s just bizarre and funny how many different reactions there are. Honestly, I feel a little guilty when people come up and ask me if it’s a real race car and they know the fake history of it from following the Instagram. Stuff like “Oh yeah, this guy raced it here and he crashed it” and I’ve got to tell them Santa’s not real. The application for the Bridge asked for race history on the car and any events that it’s won or attended. So I filled it out with a full history like “1967 Le Mans, finished 29th, 1968 Le Mans, retired with oil pump issues” and I was expecting them to give me a call and say “Dude, none of this is true!” But it somehow made it through, so I don’t know if that info is going to be a brochure or somewhere, but I’m looking forward to that fake history making its way out into the world like that.

The car looks wild, but you and Iliya are fundamentally trained car designers that work on major projects for OEMs and race teams. How does it handle, how does it feel? Does it deliver on what it looks like?

With this project, we were liberated to do whatever it is that we wanted to do. As OEM designers, we normally have to design around someone who’s 6’ 4” and 240 lbs; those jobs need to fit the ninety fifth percentile basically. The Half 11 project was never supposed to be a big thing; it was supposed to be me and my brother building a car in our backyard that maybe no one would ever see, but it was our dream, you know? It obviously grew some legs and became a bigger deal, but it was a pet project, so it was designed around my brother and I and we’re like 5’ 7” on a good day – so not many people fit in it, but once you’re in it, it’s super comfortable. We don’t design cars that don’t work, so our very first track day, I was driving the car and we basically ran about half a second to a second faster than the new McLaren 720S or the Porsche GT3 RS. The thing is blindingly fast, and I think it’s capable of being much faster, but it’s far too much car for my driving ability. But one of the goals of the project from the start was to end up with something that is terrifying and scary to drive, just like race cars were in the ‘60s. We accomplished that; it’s way faster than my abilities and it’s not just a piece of sculpture or a SEMA build. You can drive it on the street, but when you go to the track, it’s literally as fast as the modern supercars.

What are some of the details on the Half11 that you think the layman misses? It’s obviously an over-the-top looking design, but as pro car designers, I’m sure there are subtle design elements and touches that most of us are missing that are important to you two.

That’s a tough question. It’s hard to say because I’m very critical of it myself, and being the artist. I’m my own worst critic and there’s a lot of things that we need to fix and address for the next round of cars. The project that we did recently, the Hoonipiguses – which was the Pikes Peak car we designed for Hoonigan – was a car we basically needed to make look as much like a 911 as we could despite the car’s crazy package. So if it looked like a 911 at all, we actually succeeded. We weren’t trying to make an exciting design and we weren’t trying to reinvent the wheel in terms of design, we were just trying to make it look like a 911. From the public reaction, it seems like we succeeded in that despite the extreme and radical package of a Pikes Peak car. With Half11, it’s the same thing; the amount of work and finesse, and the reinvention of the lines and we had to do to make it look 911-based and retain that visual DNA, was massive. The Half11 really has nothing to do with the 911 ultimately. It is as extreme a build as you could imagine: The entire dash section’s been cut four inches down, The frame’s been cut down. The driver position has been slid forward about eight inches. The biggest compliment anyone can give us, or the biggest success for us, is that it still looks like a 911 despite being almost 14 inches wider than the 911s on each side. That’s what we’re most proud of and I don’t know if people realize how much finesse or work that took.

How did you guys get involved with the Hoonipigasus and was that project a byproduct of the interest people have in the Half 11 at all?

That project is one we developed together with Joe Scarbo, who also engineered the Half11. We designed that car about years years ago, and his idea is to make street cars out of them – which is nuts and would be the craziest 911 ever! We heard at one point that a company had come in and essentially bought the rights to the design and we needed to redesign it to accommodate four wheel drive and some other package features, and it turned out it was Mobile 1 and Hoonigan that had bought it. So when we were working on it, we really didn’t know who the person was, all we knew was that we’re going racing at Pikes Peak and we’re going to try and set a record.

You guys also have worked with Acura’s racing program and been involved with designing their IMSA DPI car. Tell us a little bit about that and how you apply the fundamentals you’ve learned from actually going racing and designing true competition cars to the Half11.

Honestly, the Half11 has zero application of the things that we’ve learned designing race cars, other than on the mechanical side. On the aero side, we were very deliberate to chase a 1960s look and aero packages didn’t really exist then; nobody really knew what downforce was. People were just starting to kind of experiment with wings, but they were putting them in weird places and no one really knew what they were doing and we wanted to capture that look. So very early on in the design, we deliberately discarded any aero, but we did run aero tests to confirm we weren’t creating a car that was going to be some awful monster to drive. We sent out the data and the guy analyzing it said “it’s actually not that bad.” While it’s deliberately not a modern solution, it works and can be controlled. So it’s not a death trap. But when you work with real aero teams for competition cars, design takes a backseat and you need to put your ego away in those situations and help the team be fast and win. There’s many ways to design a car, but I think a beautiful race car is going to be a fast race car, usually.

Working with Acura on the previous generation IMSA car, my brother pretty much handled most of that. There were a lot of areas that we couldn’t touch simply because they’re very aero sensitive or the company doesn’t want to invest the money to change things too drastically. Really, the challenge was in how do we get Acura branding and visual queues on this thing without fucking up the aerodynamics. Iliya came up with that really cool double bridge with the floating headlights. Honestly, any car that’s designed well, whether it’s the Half11, the Acura DPI car, or the Hoonipigasus, comes down to a really good team that has really good communication behind-the-scenes from an engineering point-of-view and a design point-of-view. You have to have no filter and really open lines of communication in these situations and you can’t be scared to offend somebody by saying “Hey, that looks like shit, why don’t we just do it this way?” Those guys will almost always be game if a visual touch doesn’t negatively impact performance.

What do you think is missing from modern auto design? Oilstainlab has designed a lot of concept cars for OEMs, and a lot of hyper-futuristic ones, too. I can imagine someone that put the time and energy into an outrageous project like the Half11 on nights and weekends has some serious opinions as well. What’s your take?

It’s hard for me not to sound like a jaded car designer, but the reality is that car design has reached a point similar to furniture design in the ‘70s and ‘80s, where we can do stuff that’s different, but it’s always just adding more stuff. There’s never really a focus on cleanliness or brevity or simplicity in messaging or forms or language or anything. So in the end, what we often get is a really hot mess. When you look at a lot of the modern supercars, it’s really hard to tell what the overall design’s message is. Is it about all-out performance? Is it styling? Is it fashion? Is it just sex appeal? All those things just get thrown into a blender and you get these hot messes of cars lately. I think technology should enable us to enjoy more simplicity, but unfortunately the people that make the decisions are oftentimes seduced by the complexity or the bling factor or more surfaces, more functions, more everything. It’s similar to technology, where your cell phone is never going to have less functions than it has now. There’s no phone company that’s coming out with a product today and saying “That’s it! It’s just a phone.” But that’s what we need. If you love driving, you just want to drive the car, and you don’t necessarily want all the other stuff like touch screens and features on features. Unfortunately, that’s not the commercial world that we live in.

We’ve gotten away from tactile experiences and the simplicity of just engaging with things for the pleasure of it, and I think that’s especially prevalent in the car space. If you’re not taking it to the racetrack and every two liter engine with a turbo on gets 50 mpg these days, can we at least make things that look cool?

I wholly agree with that, but once you get into a big company and consumer clinics, and strapped to the wheel of having to have best-in-class interior room or whatever every single model year, everything is forced to evolve for better or worse.

(Real life) photos by Cooper Naitove (@mrjuicebox on Instagram)

Find the Bridans and Half11 at Oilstainlab.com and @oilstainlab on Instagram

Check out 'Reference Tracks' our Spotify playlist. We’ll take you through what’s been spinning on the black circle at the C + T offices.

Never miss a watch. Get push notifications for new items and content as well as exclusive access to app only product launches.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates and exclusive offers